[an error occurred while processing this directive]

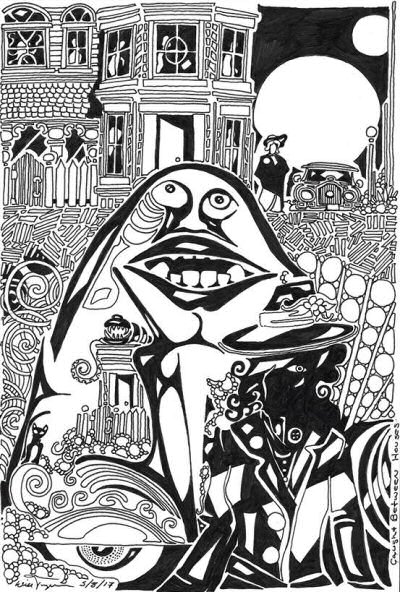

Artwork: Caught Between Houses by Will

Jacques

Mother Ate

Clare Diston

Mother called the children for dinner. They skittered into the kitchen and picked up their spoons even before they had sat down. Grandmother, stooped and long-fingered, followed behind. The children squeezed together to make space for her. As they sat, pressed knee to knee to say grace, a few flakes of evening snow crept through the cracked window frame and flurried in the air. The hairs stood up on the children's arms as they prayed. Grandmother, silent, pulled her shawl more tightly around herself.

“Watch out,” said Mother, standing to lift the first steaming ladle from the pot and passing it over bare, outstretched hands to the youngest child's bowl. She served each of them in turn, youngest to oldest, and Grandmother last of all. The old woman thrust out her bowl in shaking hands, and when Mother poured, a little of the broth splashed onto Grandmother’s wrist, licked up soon after by her eager tongue.

There was not enough for a second round from the pot, not even enough for a complete first. Mother left her own bowl empty and sat down.

“Aren't you eating?” asked Grandmother.

“I had mine before you came in,” lied Mother.

“You really should eat with the family,” said Grandmother.

She hunched over her bowl. Mother watched as the steam curled up into the old woman's face and over her shawl-covered shoulders. Did she sit like this, Mother wondered, so that her hair and clothing would smell of the food after it was gone? The idea sent a shiver down her back. Grandmother's fingers hooked the spoon and her lips curled back to receive the broth even before it was within reach of her mouth, revealing a glistening tongue and the razor-tips of two teeth.

On either side of her, the children ate. Their bowls emptied quickly and then they sat, fidgeting. The old woman ate slowly, so that when the children had finished she still had half of her portion yet to eat. The older ones tried to concentrate on anything else: the snow, the tabletop, the cold. The youngest children stared at her with desperate eyes, but there was no leaving the table while Grandmother was eating.

The chewing cut through Mother like an insult. Grandmother

rolled the food around in her mouth like it belonged there. Her lips

smacked and her tongue flicked between them; a drop slipped out and

sat, glistening, on her chin. The old woman relished each bite before

swallowing it, insipid though it was, and drew out every morsel of flavour

while the children sat hungry beside her.

Mother lowered her eyes and looked at the crescent-moon nail marks she

had gouged into the palms of her hands.

***

It was Father who let Grandmother in.

She arrived on a Sunday evening, when the children were already tucked up in bed and Mother and Father were sitting by the fire in the tiny living room. Her knock was more of a flutter, like an animal brushing up against the door, so Mother and Father weren't entirely sure they had heard it. When Father opened the door, cold air whipped into the room and made the flames shudder. There was Grandmother, looking up at them from the darkness, with just a shawl wrapped around her shoulders.

She was nobody’s grandmother, really. Instead she was Father’s aunt, more acquaintance than relative. She lived across the moors and they saw her only rarely. Her large, empty house frightened the children and Father would always come away tired, so Mother tried to keep their visits infrequent and brief. Usually the old woman hired companions – young men who would read to her, brush her hair, feed her – but just recently the money had run out and she had been forced to trust to the kindness of her relatives. Mother couldn’t imagine how she had made the journey. It would have taken hours to cross the moors on those frail legs, and the terrain was treacherous even for someone in her youth, but standing on the doorstep Grandmother didn’t even seem out of breath. When Father invited her in, she let out a sharp cry and reached up to wrap her arms around his neck. The skin hung from her bones like wings.

The old woman pulled Father’s chair closer to the fire, threw off her shawl and settled in with a sigh. Mother and Father talked with her for a while and then retreated to the kitchen. For Father, there was no question of whether she should stay; she was family, however distant and tiresome. Mother reminded him of his dwindling work and their shrinking meals, how the old woman had never done anything for them, but he would not be moved. She would sleep on a mat in the pantry; she would be no trouble at all. It was decided. Even so, when he went off to bed, Mother thought she saw a pleading look in his eyes.

For six months Grandmother followed Father around the house, from the moment he returned home in the dying light to the minute he crawled, exhausted, into his bed. She plied him with questions and waited, wide-eyed, to suck the answers out of him. What had he done today? How much food had he brought home? How was he earning his money, and how did he expect to earn more? She would not be satisfied until he had emptied out every part of himself for her delectation. His plans, his ambitions, his disappointments – she nipped and squeezed and clawed until they seeped out from under his skin, and then she licked them all up and smacked her lips with pleasure.

Mother tried to intervene, dreamed of locking the old woman in the pantry to which she seemed so attached during the day. She would stay in there for hours, silent as a church, ignoring the children and the household chores. But Grandmother could not be shamed, and if Father heard Mother being too sharp with her then he would crumple even further. So Mother kept her mouth shut and raged at the old woman only in whispers when she was alone.

The months took their toll. Father grew thin and drawn. Soon he began to wheeze like the old woman was drawing even the breath from his lungs. It was Father who let Grandmother in, and it was Father who died.

***

The cramping of her stomach woke Mother in the night. She curled into a comma, reached out her hand into the empty half of the bed and gritted her teeth. After a few minutes the hunger pains eased enough that she could unfurl herself, but when she stretched out her legs she found the end of the bed had gone cold. She sighed. A streak of moonlight fell across her pillow.

As she lay there, willing herself to fall asleep before the pain returned, she heard a small noise from somewhere in the house. It was so quiet as to be barely there, but still it was enough to make her widen her eyes and sit up in bed. She tucked her hair behind her ears and breathed quietly through her mouth. Minutes passed. Silence dragged itself along the floor of the tiny room, climbed the walls, pressed its hands against her ears. Then there was the noise again.

Mother slipped out from under the blanket and tiptoed to the bedroom door – never closed, in case the children needed her. The windowless corridor should have been all-engulfing black, but at the far end light spilled around the edges of the ill-fitting pantry door and lit up the corridor with a feeble glow. Grandmother was awake.

On silent feet, Mother crept down the corridor, past the children’s room, and paused for a moment to look in on them. The light of the moon revealed them in their one big bed, their faces softened by sleep, curled against each other like fish in a basket. Lying like this, from largest to smallest, they looked like a timeline of their father’s decline. Mother bit her lip and passed by.

Outside the pantry, she pressed her eye to a crack in the door. In the flickering candlelight, the pantry seemed to move like the hold of a ship. The walls were windowless, covered instead with close-packed wooden shelving that pitched and rolled under the shifting candle flame. A thin mat covered with a blanket was pushed right up against the farthest shelves, and just in front of it stood the candle in its holder. The shelves were all but empty, save for a few jars of herbs and condiments, and several rinds of cheese and hunks of bread. There was no more meat; they had eaten the last bone-scrapings of it in that night's broth.

Grandmother crouched over the candle so that it threw grotesque shadows across her face and shoulders. The old woman's lips were curling, her mouth glistening with something wet and sticky. In one rheumy hand she gripped a jar of honey, almost empty, as her other hand dipped inside and carried the dregs to her lips.

Hunger, rage and candlelight made Mother’s head reel. She clenched her fists and flung the door wide.

“How dare you!” she spat.

Grandmother looked up, her hand halfway to her mouth, a drop of honey clinging to the tip of one finger.

“There are children starving in this house. Look at yourself!”

A smile began to creep across Grandmother's lips and the tips of her teeth looked even sharper in the wavering light.

“Aren't you going to say anything? You've been caught, you... you... thief!”

Grandmother said nothing, but she kept her eyes locked on Mother as she brought her hand to her lips and sucked the last of the honey off her fingers.

An unearthly scream came out of Mother and she took a step towards the old woman, close enough to feel the candle’s heat on her bare legs. Then she lifted one foot, placed it squarely on Grandmother's chest – fleetingly thinking she might feel the old woman’s heartbeat, but there was nothing – and pushed as hard as she could.

Grandmother fell backwards against the lowest shelf. The wood, worm-eaten and rotten, gave immediately, splintering into fragments that shone with her blood as she tried to pull herself away. Her nightgown was torn, her back lacerated. Mother raised her foot again, drove the old woman back against the shattered wood and pinned her in place. Ground her into the shards.

Grandmother did not scream, but groaned like a bellows emptying of air. She raked her fingernails along Mother’s leg until she drew blood and bent forwards at a weird angle, her mouth working frantically so that Mother was sure she would have bitten her if she could. As Mother pressed and pressed, a spray of red erupted from Grandmother’s mouth, and the wet sounds of throat and tongue and lips were a grotesque imitation of the noises she made when she ate.

After a few minutes, Grandmother fell still. When Mother removed her foot, the body slumped forwards and fell to one side. The back was even more bloodied than before, and in amongst the scratches was one wound that was deeper than the rest, just beneath the left shoulder blade. The shelf she had fallen against was not rotten all the way through. One ragged splinter of wood, hard and pointed, had driven deep into Grandmother’s heart.

***

Mother called the children for dinner. This time no hunched figure followed them to the kitchen. They sat, no longer tightly pressed together, and bowed their heads to say grace. Tonight the snow did not flurry through the crack around the window, blocked as it was with a wadded shawl.

“Watch out,” said Mother as she picked up the ladle and they held out their bowls to receive the steaming stew. The children licked their lips. She served them all, youngest to oldest, and then she went round the table again. The children's eyes grew wide. “Eat,” she said.

The stew, which had been brewing for hours on the stove,

was rich and red and meaty, and the children made happy noises when

they tasted it. Tonight they would sleep without pain. Mother dug into

the pot and filled her own bowl. Then, with a final look around the

table, she bowed her head and ate.