[an error occurred while processing this directive]

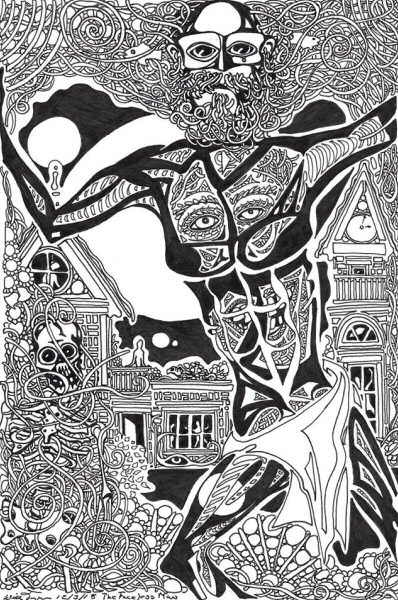

Artwork: The Faceless Man by Will Jacques

The Unearthed

Scott D’Accordo

With his eyes closed, elbows on the desk, Kevin Graf sat holding his

downcast head at the temples with cupped palms. He wanted eighth period

math to begin and end. He wanted to get home, sneak in a nap, but then

he remembered chess club, remembered his match, dropped his head lower.

Mom had been fitful the night before, had needed his help getting to

the bathroom four times.

Someone said “Kevin,” but he thought the voice unreal. It definitely wasn’t his math teacher Mrs. Menard. Class hadn’t started, and she’d given up calling on him anyway, given up trying to break his “trances,” as he knew Mrs. Menard had described them to his sister Allie.

“Kevin,” the voice hissed now. “You deaf?”

He opened his eyes, lifted his head.

Jodi sat in the row directly to his left but up two desks. She smiled at him. He hadn’t heard her come in. He hadn’t heard her friends, who’d materialized at their own desks nearby. Almost the entire class had materialized.

Jodi displayed her textbook’s neatly wrapped brown-paper-bag cover, where she’d doodled florid declarations that Jodi hearted Kevin. In other spots she’d paired her name and Kevin’s with a plus sign. She was dating Kevin French, not Kevin Graf, and her audience of friends must’ve understood the irony. Because they laughed.

Jodi licked her lips, mouthed something that Kevin didn’t quite grasp, and arched her back to accentuate her prematurely generous breasts. But still, her farce depended mostly on pointing at the name Kevin on her book and then at him.

He had noticed a greeting card on her desk. Now he saw her reach for it, but she pulled her hand back.

“You were about to throw that Valentine’s card French gave you into the joke,” Kevin said. “But that wouldn’t make sense. I know I didn’t get you a card.” He’d never stood up to Jodi.

The opening bell. Jodi and the other girls turned toward Mrs. Menard. Kevin returned to his trance. The final bell.

He put on his brown leather jacket, too small and worn away to white at the elbows and shoulders.

“What happened to your coat?” Jodi said, loud enough for the others to hear. She still flirted artificially, caressed his left shoulder--the jacket’s point of greatest erosion to white.

“I’m always leaning on things,” he said.

Two hours later, only Kevin, his opponent, and Kevin’s English

teacher Mr. Varick, serving as arbiter, remained in the classroom designated

for chess club. The last of the other matches had ended over a half

hour ago. Kevin was a sophomore and his opponent a senior, but still

Kevin stressed about not ending the game sooner. He didn’t know

why. Varick’s opinions on chess didn’t matter.

When Kevin finally won, the senior muttered his way out of the fluorescent room. Kevin felt little gratification. Victory meant not triumph but relief. Victory meant not losing what was already yours.

Varick bounced out of his chair. “Nice game. Heard your mother’s a master. International?”

“No, not an IM. She just missed,” Kevin said.

“Still impressive. Get into some battles?” Varick said.

“She’s got Parkinson’s. Dementia.”

Kevin had already told Varick about Mom’s condition, but he didn’t look embarrassed at having to be reminded. “So she never plays at all? Maybe it would help…”

Kevin shook his head. Varick didn’t need to know that a few months ago Mom had gone into the basement and retrieved the electronic chess set. The set inviting you to compete against all levels, from novice to master. The set Mom had bought Kevin the prior Christmas, having forgotten he already owned the exact model. Varick didn’t need to know that late at night in bed, with the board propped on her lap, she’d been playing against the easiest level, often taking forever to make a legal move.

“Your sister Allie was in my class. How many years ago was that?” Varick said.

“Eight.”

“She was something. Smart. Tough. Own her own business by now? CEO?”

“Never finished college,” Kevin said.

“What the hell happened?” Varick said.

“Things got in the way.”

Alone in the high school’s Industrial Arts Wing, Kevin rolled

his combination, popped the latch, and saw his disheveled hair reflected

in the small magnetic mirror on the inside of the locker door. He realized

he hadn’t looked in a mirror all day, not even before leaving

the house. He smelled his armpits and confirmed that he’d forgotten

deodorant, again. “What’s wrong with me?” he whispered

out loud.

He wouldn’t attempt most of his homework, so he grabbed only his gloves, winter cap and the book of short stories. Varick had assigned “Silent Snow, Secret Snow”: Kevin didn’t know the story, but its title whispered. He put the Valentine’s Day rose--purchased for two dollars from an unenthusiastic student council member--into the inside pocket of his jacket.

Student projects covered the walls. Kevin thought he knew every one of them, but at the end of the hall, with the wind testing the heavy black doors, there was a surprise--a painting of a tuxedoed man in a tree. He sat on a thick branch, his ancient face sunken and anguished, his head bald, eyes large. Twelve German Shepherds made a circle around the trunk like numbers on a clock. They aimed their foaming muzzles at the man’s unreachable feet. A signature at the bottom identified the artist as Stanley Tepper, class of ’79. Why hadn’t the picture been there before? If it had, why keep it on the wall for eleven years? A manic shudder pressed Kevin through the doors and into the evening.

He blew into his gloves and peered down the path lined with a chain

link fence on either side. The verdant branches of the overhanging evergreens

beat like lethargic wings, their shadows engulfing the pavement between

the parallel fences. Kevin had never crossed the park after dark, but

it cut his walk by ten minutes. The moon broke from huddled clouds,

pouring alabaster on the suburban street and glinting off the sounding

windchimes on the porch of the nearest house. He walked up the path.

Spit out onto the park grounds, he started toward the baseball diamond, toward the open expanse of outfield that held no homerun fences, toward deep right center, beyond which there was another path to another street.

But before he reached fair territory someone said “Little help?”

Kevin stopped. A man stood inside the webbed hemisphere of the jungle gym next to the field. This stranger gripped the metal bar above him, his elbows bent, relaxed. He was a young man, but his clothes were styled from the late fifties or early sixties. His hair was a dark crewcut. He wore a turquoise and white rockabilly shirt, black jeans rolled at the ankles, but no jacket. A rusty shovel stood in the sand behind his bare feet.

Kevin walked closer, close enough to see, with the help of the moonlight, the stranger's crystalline irises. Irises not windows but mirrors.

“Quite a game you just played,” the man said.

Kevin wanted to turn around, run, but he couldn’t move.

The man laughed, put his hands behind his head in mock submission, walked backwards to the center of the jungle gym. “Don’t be afraid…yet.” He pulled a pint bottle of Old Forester from his hip pocket and shook it invitingly. “Slug?”

Kevin shook his head. “My father drank Old Forester.”

“And your mom never cared for bourbon,” the stranger said, then took a slug. “That a chess book?”

“Short stories.”

“I got some stories, but brevity’s never been a strength.”

“What’s the shovel for?”

The man stepped aside with the flourish of a magician, maybe a matador, to reveal the far side of the dome’s sandy bedding. Somehow Kevin expected to see the ditch surrounded by small mounds of sand.

The stranger stepped into the ditch, the level of the ground not surpassing the middle of his thighs. “Can’t go any further,” he said. “Earth’s frozen.” He scanned the sky, whiffed the air. “But it smells like snow. I’m burying myself, but I can’t do it myself. If I lay down like a king high, we’ll have no problem.” He took another swig. “Some folks go easy. Dogs at the jugular get you quick. But other folks get torn limb from limb by dogs climbing that tree, fangless dogs getting into that tree and--”

“Dogs don’t climb trees,” Kevin said. He thought of Stanley Tepper’s painting.

“I meant a cat. A cat’s a better analogy, and never mind any tree. Just a cat that plays a long time with its kill--a mouse let’s say. You a mouse?”

Kevin stared hard into those impossibly reflective eyes. “How do you know my parents?”

“I don’t suffer questions people already know the answers to,” the stranger said. “That pancreatic cancer’s a bitch. Feel guilty about your pop?”

“Why would I?” Kevin said.

“Making this difficult?” The man held the bourbon bottle in one hand and unbuttoned the bottom of his shirt with the other to expose the right side of his torso. Something shaped like a small crab with a long, vertebrate tail undulated below the skin. “That rattling sound means it’s eating. Incurable. Wiseass buddy of mine says it’s my liver unmoored and amok.”

Kevin had to look away from the stranger’s side, so he looked again at his face. Kevin almost flinched at the pain there, its apparent sincerity. “I can’t help. Late for dinner.”

“You that hungry?” The man took a drink.

“Not sure.”

“You’re drifting. Keep those eyes on mine. And if you’re not sure whether or not you’re hungry, you ain’t.” The stranger screwed the cap on and put the bottle back in his pocket, rebuttoned his shirt. “How’m I going to finish this job?”

“I’m sorry,” Kevin said. “My sister’s over. She’s cooking.”

“Sister?” The man snorted. “Moved out, went and got hitched on you. A baby can’t be far off. She tries, does her best…”

Kevin starting walking backwards.

“Where you going? Your father suffered. And your mother. Think it’s bad now?” The stranger spat. “I have her chess clock. It’s not right.” The digital timer appeared in his hand, like he’d had it palmed. He stared at Kevin, set the clock without looking at it, then clicked the activation toggle. “Your go.”

#

Kevin had thought Manhattan a long way, especially since they played every day in the recess off the den they called the chess room, which he knew normal people like Allie and Dad had called the piano room on account of the Baldwin against the wall. But, when he was eleven, a few weeks after Dad died, Kevin’s mother took him on the train from Long Island to the club on West 10th Street.

The Armenian woman behind the counter smiled and said “This must be the prodigy.” It was the second time he’d been called prodigy in only two months. After the first, Kevin had looked up the word in the dictionary, had grown suspicious of its meaning.

After Kevin and Mom set up at a table, after their opening moves, she told him chess has “no tough breaks, no luck, no acts of God.” He felt her reading his doubt. Before moving the queen she’d picked up with her thick, unadorned fingers, she gestured to two men playing each other in the red-leather-backed booth in the corner. Kevin recognized the younger of the two--a sallow, haunted looking man--as a Grandmaster. Mom said she wouldn’t beat the man once in twenty games.

It had seemed a long way to go to make that point.

#

Allie was tall, slight, austerely pretty. She’d made chicken cutlets with rice pilaf. Kevin sat on Mom’s right, Allie across from Mom. The kitchen’s floral wallpaper had faded, frayed, peeled. Allie’s husband Henry hadn’t shown again. She said he had to work late as she poured herself a third glass of claret; Kevin was counting. She looked at him. “You’re grimmer than usual. What’s your problem?”

Kevin felt like asking you think I have only one? He felt like telling her he’d met a man at the park trying to bury himself, but decided that his sister’s worries about his mental state were too much for the health of her own. “Smells like snow,” he said.

“Why’d you walk in this weather?” Allie said. “I would’ve gotten you.” She turned to Mom. “See the rose Kevin got you at school? It’s Valentine’s Day.”

“Yes. They’re nice,” Mom said, her face fixed, rigid. She continually turned her tremulous left hand from palm up to down.

“They’re nice?” Allie said. “There’s one flower in that glass. You see more than one flower?”

“I saw two at first, but…” Mom’s voice lacked inflection, had grown so much softer.

“The rice is good,” Kevin said.

“That happens when you follow the recipe,” Allie said, probably referring to Mom's latitude with suggested amounts of ingredients. Kevin thought these liberties didn’t agree with all the chess openings Mom had memorized. Or maybe they did, maybe there’s only so much adherence to what’s correct a person’s mind can hold. Maybe Mom didn’t care. She’d once said: “There are two types of food--edible and inedible.”

A small golden spider descended from the blue petal of the flower-shaped lamp above the table. A lot of them lived up there, and they’d become frequent dinner guests. To Kevin, they were paratroopers who had the advantage of climbing back to the plane. Mom clearly noticed the spider, too, her face transfixed, childlike as it landed on the edge of Kevin’s plate.

“Spiders on the table,” Allie said. “This place is getting gothic. Can’t even have friends over…if you had any.”

“He does,” Mom said, struggling for a name. “Richie. On Beacon Lane.”

“Moved two years ago,” Allie said. Two years ago, Allie had been engaged, seldom home. Mom wasn’t sick then, at least hadn’t been diagnosed. One night, Mom had ordered Pudgie’s fried chicken and crinkle-cut french fries for Kevin and her. No conversation until Mom, dressed in something between a kimono and a bathrobe, told him she’d kill herself if he wanted her to. He took it to mean that she would do anything for him. But why hadn’t she just said that? Why hadn’t she changed out of that robe, made dinner once in a while? Even if her cooking didn’t taste as good as Pudgie’s, even it was just edible.

Now the spider crawled the rim of his dish. “There’s some spray in the garage,” he said.

“Since when do you kill spiders?” Allie said. “Kill anything?” She seemed to catch the harshness in her voice, because she softened it when she said, “I’ll do it.”

Kevin looked at Mom. “Won my match today,” he said, “opened with Queen’s Gambit. He accepted.”

Mom’s eyes followed the spider around the perimeter of his plate.

“Mom?” he said. “Queen’s Gambit?”

“Queen’s Gambit,” she said. “Fine vs Lasker, 1936.” Mom hadn’t been born in 1936, but it must’ve been a game she’d studied, probably memorized.

“I’m thinking about getting someone here nights,” Allie said to Kevin. “Yelena’s great, but four hours during the day isn’t enough. She gave me the name of her friend…Vera or something. Says she’s very good, not registered, but good.”

“Don’t talk around her like…” Kevin said. “Don’t talk like she’s not here. She understands more--"

“This Vera could stay in my old room. Give you a break when Mom wakes up, has to use the bathroom, if she needs…anything.”

Another aide could help, especially overnight, but Kevin didn’t like the idea of another stranger: he still considered Yelena a stranger. He had often thought of what Mom would say if she were healthy again, but he could never say it. He tried now. “You’re thinking about getting someone here nights? Maybe you’re thinking we can outsource all of our problems to the Soviet bloc. Intrusive. Expensive. No.”

“Where the hell’d that come from?” Allie

said. “It would be expensive. But I just got that promotion. Henry’s

doing well at the restaurant. We still have a little of Dad’s

insurance. You turn sixteen in what…two months? Maybe you could

get a part-time job.”

“I’ve got school. And chess,” Kevin said, still doing

his best to say what Mom would have, relieved he hadn’t referred

to himself in the third person.

“Chess?” Allie said. She hadn’t played once in her life, never even learned the rules. To Kevin she seemed almost alien in that, but he probably seemed alien to her in his tone deafness. In what felt like a long time ago, Allie had improvised on those Baldwin keys, had played piano like Dad, well, not like Dad: she’d played better, Kevin somehow knew.

He broke free of memory. “Varick says I’m getting pretty--"

“Chess!” Allie said. “Mom can’t get out of bed, can’t get back in. You’re okay waking up how many times a night? You’re a zombie at school. Your teacher told me. Told me.” Allie poked her long, nail-bitten forefinger to her sternum. “You’re also kind of like a zombie at home. A job will get you out, force you to interact. Ten hours a week.”

This suggestion of increased socialization made it easier to summon his idea of Mom's healthy, strong perspective. “No. And as far as the babysitter, also no.”

“Since when do you have…” Allie swallowed her wine. “Okay. Let her fall down the fucking stairs.”

“Don’t curse,” Kevin said. He was rolling now. “I have a problem with people outside a situation telling people inside a situation what to do. And where’s Hank tonight? This place getting too…gothic?”

“I’m in a fucking insane asylum,” Allie said.

“Don’t curse!” Kevin banged his hand on the table, startling even himself. Calmer, he said “Not at dinner.”

“What’s the point?” Mom said.

Kevin didn’t know if Mom spoke in the moment, or if she was repeating something they’d all heard Dad say four and a half years ago, after the doctor had suggested more chemotherapy. They’d already pumped him full of that poison, almost destroyed him along with most of the cancer, which came back. Dad was ready to go, had knocked over his king, but even without more chemo he had to keep playing, had to endure an accelerated yet ruthless endgame. When Dad died, Kevin cried with loss and relief, relief that it was over. He’d eventually looked up at Allie, not quite nineteen at the time. Her eyes sheened but dropped no discernible tears. And he had admired her, her toughness, had admired what he was not.

Now, Allie poured herself a fresh glass of wine, slumped back, receded into her chair. “We’ll talk about it another time. Another time soon.”

Kevin thumbed the spider on his plate, gave it a fatal twist.

Mom hadn’t noticed putting the cordless telephone receiver in the freezer that morning, but she clearly noticed her son’s arachnicide. She looked hurt.

“So much for not killing anything,” Allie said.

“A paratrooper who should’ve gone back to the plane,” Kevin said, speaking as himself again, wiping the tiny corpse from his thumb. “A stranded soldier. Instead of allowing him to get captured, tortured, I helped. Like those cyanide pills they give fighter pilots.” He slid his plate away, asked to be excused.

Allie excused him.

Kevin lay in bed, but sleep wouldn’t come. He got up, turned on

his television--a black and white thirteen inch without cable--and clicked

to a gameshow. A man resembling the gaunt Grandmaster on West 10th spun

a wheel, waiting for luck… Maybe Mom had seen her own illness

as the Grandmaster in the corner, the one she wouldn’t beat once

in twenty, once in a thousand. Maybe Mom had planned to tank a few moves

to end her game even quicker. But this was a different disease. Would

she know she was sick anymore? Was her new reality telling her that

everyone around her was sick or crazy or both, that she was the sane

one?

Kevin shut off the TV and got back in bed. Trying to conjure thoughts more conducive to sleep, he continually replayed the match he’d won that afternoon in his head; he’d considered a queen sacrifice in the middle game that almost definitely would’ve won it for him, won it faster at least, but he hadn’t seen it all the way to checkmate. He couldn’t see it through now either, but it didn’t matter, because he started to drift, Manhattan not seeming far at all to make a point. He found further comfort in Mom’s words from four years ago: no tough breaks, no luck, no acts of…

A click sounded him awake and he saw the band of light under Mom’s closed bedroom door. He heard a series of beeps, moves correctly applied, then the electronic voice told Mom she’d attempted an “Illegal move.” She tried another. “Illegal move.” Kevin pulled his pillow around his ears, but more frustrating, “Illegal move.” He threw the pillow, turned to the wall, eyes open. “Illegal move.” He wished she were just asking for help using the bathroom.

Kevin got out of bed, put on his jeans, his sneakers, slipped out of his room, down the hall, the steps. He pulled his jacket off the bottom of the banister and grabbed a flashlight from the hall closet. He stopped. Listened.

Another “Illegal Move” came from Mom’s room and pressed him out of the front door.

The moon hid behind the overcast. Kevin pointed the flashlight. The

man already lay in the grave. Kevin slipped through one of the triangular

interstices of the jungle gym and snatched the shovel from the man’s

outstretched arm. Mom’s digital timekeeper lay on the sand by

the stranger’s head like an alarm clock, only facing away: the

left side, Kevin’s side, read 0:00:00; the right side, the stranger’s,

read 0:53:54.

“You said the clock isn’t right, doesn’t work,” Kevin said.

“You know that’s not what I meant.” The man drained the last of the bourbon, screwed the cap, and put the empty bottle back in his left pants pocket. “Thanks for doing--"

The rattle from inside the man’s body interrupted. He moaned and turned his head away. The rattling ticked slower, slower, stopped. “One more favor? Before you cover me with that sand, take the shovel and hit me over the head a few--”

Thwack!

Kevin slid the shovel and flashlight under the bed, removed all his

clothes, got under the blanket and gazed up through the window at the

snow, mute and serene, unlike the blathering rain. He wanted sleep,

deep sleep, dreamless sleep covered by inches, feet, yards of snow,

a sleep from which he might never be unearthed.

Instead, a half-slumber followed. He dreamed of things Stanley Tepper, class of ’79, orchestrated: a circular clearing in the woods, a man in a tree. Kevin dreamed of dogs with no teeth, dogs with the arms and legs of human beings.

He woke after five, knelt on his bed like a child to look out of the window at the snow’s progress--only a dusting that hadn’t defeated the spiking yellow grass on the front lawn. He lay back down. That click again and that band of light under Mom’s door. That electronic voice. That same command. Again. Again.

Kevin went headlong under his bed, knocked the flashlight

out of the way and reached. The shovel was there.

Home