[an error occurred while processing this directive]

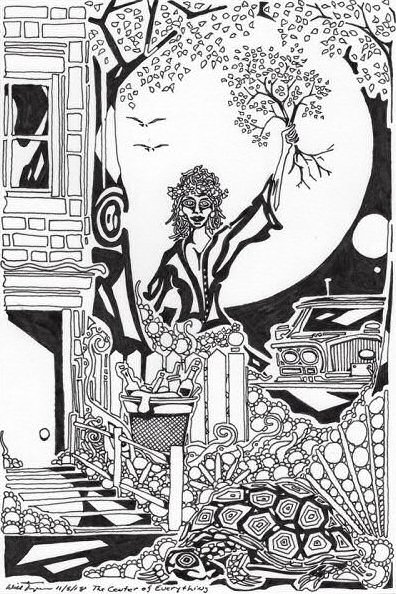

Artwork: The Center of Everything by Will Jacques

Bredenbruch

Andrew Hart

“Drive me away with your barking, watchful dogs;/ Allow me no rest in this hour of sleep./ I am finished with all dreams./ Why should I linger among slumberers?” (A translation of a German song)

Little did I think that I would spend my latter years hidden away in a small German town with a man who I barely know, avoiding churches and priests and fantasizing about the owner of Cafe Schubert, where I play the piano and drink coffee. In the mornings I teach at home to smartly dressed Frauleins and their mothers, who have heard – God knows how – that I was once a great performer. They cut lessons short in case I am tiring myself and drop round sustaining soups or lavish cakes to our door, which I devour greedily before Grischa comes home, or pass off as my own cooking.

In the evening I watch television whilst Grischa prepares his lessons for tomorrow and then we might go out and have a drink and walk around the Stadtplatz, Grischa saying hello to everyone we pass; he seems to know them all, whether they be pupils, their parents or his friends from his youth or friends of his mother and father. It is as if nobody has ever left here, nobody has ever died.

Grischa has lived here all his life, and his parents, grandparents and great grandparents before him going back generations, so that they are a part of the fabric of this town. Everyone knows who he is, and as he is kind and patient, he is a popular man in this town, whereas I am a mysterious stranger from England, who does not quite fit in, an oddity, but tolerated for the sake of Grischa.

I met him in Cologne; I was just travelling, escaping from the cries of my children and husband. I had left them in the house, sat at the dining room table, unmoving, whilst I grabbed my bag, which was lying waiting for me, already filled with clothes, my passport, my flute and my favourite sheet music. By the next morning I was over the channel and in Paris, anonymous and alone, but also happy and with a feeling of release as I wandered where I would, making money by busking with my flute and playing the piano in cafes. It was as if I were a music student all over again, with my whole life ahead of me.

Grischa found me drunk in a beer house surrounded by men whose lechery was beginning to conquer their timidity. He offered to help me back to my hotel, but ended up in my bed, between my thighs, and stayed all night. Was it guilt that led him to spend the next few days with me and then at the end of it to offer to take me to his home? And was it boredom, or perhaps even loneliness, that led to my accepting? He had told me about Bredenbruch, the small town where he taught and where his family had lived from the year dot, and something in the way he talked about the place made it sound , and anyway I needed to keep hidden and this would do for a time, I could always move on when I felt the need.

As we got ready to leave the hotel, he looked surprised at my lack of luggage.

“Where is the rest of your stuff? Is this all you have?”

I shrugged and put my bag in the boot of his car, all I had left from forty-five years of life, just the basics, but then what else does one need? Clothes, music and something to read, possessions just trap you, make it harder to keep on travelling.

The modernistic buildings from Cologne and its outskirts soon disappeared and we drove through picturesque towns and villages, past woods and fields. Grischa got tired and so I took over at the wheel, following endless and twisting roads whilst he snored quietly beside me. Bredenbruch was hardly sign posted, even when Grischa said we were getting close, there was nothing to guide us, as if it was a magical town from a Germany that no longer existed, a Germany of fairy tales and magic, which needed a spell to gain entrance. But Grisha knew the magic words and he guided me through myriad lanes that appeared to lead nowhere.

And then I gasped, because from a distance I saw my children Sam and Julie, standing, starring straight at me, whilst next to them was Pete, also looking straight at me with hurt and anger. I gripped the seat tightly and felt that I was going to be sick.

“Are you okay Leigh?” Grischa asked.

I turned to look at him, at his concerned face, it was only for the shortest of semiquavers, but when I looked again, they had gone, presumably inhabitants from the town out for a hike who had disappeared back into the wood, and who had reminded me of the family I had left behind.

“It was nothing; I am tired,” I responded, as my breathing slowed down to normal.

A few people waved as we drove into the town, past the Rathaus and the shops, which were beginning to close, and then we were at the large white house which was to be my new home. It looked ancient, as if it had been there since before the town, unchanging and eternal, more so than the adjacent church and graveyard, which seemed modern in comparison, an alien intruder into a pagan land.

Grischa teaches English at the local Grundschule, so perhaps I am just someone he can practice the language on, and help with his marking, not that he needs much help, as his English is well-nigh perfect, he even understands English humour and has an impressive knowledge of dialect and slang. I envy his pupils with their tall, smartly-dressed Lehrer, endlessly patient and kind. “Do not worry Leigh,” he says to me when I am feeling low and he finds me hidden in one of the bedrooms, “please do not worry,” and I imagine him saying the same words in the same tone to some poor pupil who is struggling with life and has nobody else to turn to, and for a moment I feel safe and at peace, as if nobody can get me.

We get on well; he makes no demands on me and seems to enjoy my company. Sex is infrequent, but I don’t mind that, rather enjoy being able to sleep alone in a bed, to wake up when I like. No longer do I have to deal with the complaints and self-righteousness of my husband and his overwhelming lust, which I failed to tame or dampen. So many bring their fates upon their own heads, not realising that we will all be punished, and that even those we take for granted can become monsters if pushed hard enough.

The sun is warm in the evenings as we leave the house, and I can smell the river, pure and clean, whilst Grischa’s hand lies protectively on my arm. The sound of German surrounds me, quiet and respectable, and there is one of my pupils, Frau Kurzweg, an older lady whose husband used to be someone important, walking towards us. She smiles at Grischa and gives me a bow and then walks on. I sense humour in her but well-concealed behind a façade of respectability. She often brings me chocolate and orange cake. which I share with the birds after she has finished her lesson.

Grischa and I sit on a bench and watch the world go by, or the world of Bredenbruch, and I munch on Ritter Sport chocolate, which I always carry with me. I offer Grischa some and he nibbles on a square most genteelly. The locals smile at us – a young couple in love.

“Guten Abend,” they say, and we return the greeting, and then we go home, arm in arm, the taste of chocolate in my mouth making me feel dry and a little uncomfortable, but I know that I will be able have a drink soon.

They are a strange lot in this town, most never seem to have left the town, never been to Cologne, let alone Berlin or Munich, or even another country. There are no newspapers in the shops and I have not seen one television since coming here. There is nothing to remind the people who live here of what is going on in the outside world; it could have all been destroyed for all I know.

“Don’t the natives ever want to go elsewhere?” I asked Grischa, “Don’t they want to travel?”

“Why? I don’t think my parents ever left; once you are here it is as if you have found where you need to be.”

“You were in Cologne; I wouldn’t have met you otherwise.”

“But I found it difficult to leave. For months I tried to go but something called me back, and then eventually when I did I found you and brought you back, so perhaps it was all fate.”

Grischa’s great great grandfather built the white house, when there were only a few other houses and a wooden church, the predecessor to the one which keeps me awake with the ringing of its bells. This used to be the centre of the town, but it has grown away from us so that we are now on the edge of things, and I wonder if we will eventually be taken over by the woods that surround this town and that seem to be encroaching upon us.

The house is large, with countless rooms on three floors, yet they are all furnished, at least in a manner of speaking, and clean, and they all have rather garish oil paintings on the walls, of landscapes, of the church next door and the graveyard, but none are of anywhere else, as if the artist had all she needed here.

“My grandmother’s,” Grischa tells me, “she painted throughout her life but never tried to sell them. When she had finished one picture she would hang it up and then a few days later find something else to paint.”

“They are not bad,” I offer, although I know little of painting.

“If we fall on hard times, we can always sell them,” he suggests, and I am not sure if he is joking.

The house smells of cinnamon and cloves and other unidentifiable odours that have permeated from all the stews and pies that were cooked by Grischa’s ancestors over the years and are now part of the very structure of the house. Sometimes when I walk alone along the corridors and into the rooms I hear the murmuring and easy laughter of the previous inhabitants of this house, like Grischa, nothing malicious or unkind, just understanding and tolerance, people who would never destroy their family because of their discontent, but would carry on with their lives, because the Bible tells them to be content with their lot, and who would never leave Bredenbruch, even if they could.

“Play for me,” he requests, and sits in what is now the music room, on a large chair, and after I have swallowed some water, I sit in front of the Grand Piano and play Chopin and Debussy. The tone of the piano is clear and strong, and the keys already know my fingers and how to respond to the faintest of touches. Grischa might not always recognise the music that I play but he listens without appearing bored, and sometimes in the mornings I catch him humming a tune that I had played the evening before. I can feel his eyes on me as I play, admiring and perhaps a little disturbed and unsure about who he has brought home, and who in such a short time has become a part of his life. Perhaps he was bored too, and despite the familiarity of the townspeople, lonely.

The customers at Café Schubert have coffee and cake, conversation and the chessboard, so my music is just background noise, or at best a moment’s inspiration whilst someone is plotting a move. Even Emre the owner, an immigrant from Turkey, who claims to love classical music, will applaud anything that I tell him is Schubert, whether it be my own compositions or sixteenth century. But I forgive Emre his ignorance, perhaps Grischa’s kindness has infected me, and after all he gave me this job, and he is so handsome – tough looking but gentle and humorous, and he clearly makes an effort with his appearance and hygiene, always dressed well and smelling divinely. I am a little in love with him in a lustful sort of way, well more than a little in truth.

Tonight I sleep at the top of the house, luxuriating under the lightest of duvets. The bedroom is small, the window is above my head, and I have it wide open and listen for the sounds of the townspeople, but all I hear is the swoop of an owl and in the far distance a car travelling to Cologne, or even further away, and on the hour there is, close by, the harsh sound of Church bells that makes me shudder. The people of Bredenbruch are either asleep or making quiet, easy love, whilst Grischa is sat in another room reading Dickens or some other “great” English writer, and then he too will fall asleep, his dreams as innocent and kind as he is.

There is a painting on the wall of a group of townspeople, four men, standing outside a shop, staring happily at the viewer. I stare at the group as I slowly drift off to sleep. I dream of Emre; as lost in this town as I am.

“Will you fuck me Emre, fuck me on the table where you serve the well-fed and arrogant? Make me shiver with joy and feel my youth once again. Make me smell as you do and take me away to the East, where we can wake together on linen sheets that smell of our bodies, drink coffee and talk of Holy things.”

I can smell his exotic hair oil that reminds me of oranges and grapefruit, as he reaches down to kiss my breasts. And then he is gone, and I can see daylight above my head, whilst downstairs I hear Grischa running a bath. It must have rained in the night, as my duvet is damp, and I hurry downstairs for my coffee, a pastry and to kiss Grischa goodbye before he hurries to school to talk about England and the English.

Frau Kurzweg comes mid-morning and plays through some Beethoven marches. As usual she appears to go through the pieces with no emotion, completely divorced from what she is playing. She hums along contentedly as she plays, this lesson just an agreeable hour between social visits, and perhaps something to tell her friends about. Despite myself, I remember teaching the piano to my children when they were young. I found it so frustrating that they just did not seem interested; both had talent, but could not be bothered, and both soon gave up in a flurry of tears, and Pete, as usual siding with them.

“Maybe they will come back to it,” ever conciliatory, “but you cannot force them to learn.”

“Why not? They are forced to learn their lessons at school. You just encourage them; they will never go anywhere,” I told him, and with that I was certainly right.

Frau Kurzweg puts down the piano lid, her time is up, hands me an envelope with her payment in, and leaves a small wax paper bag of cakes left on the top of the piano; the smell had been a distraction throughout the lesson. Before investigating the cakes I play some Mahler, filling the house with the disturbing melodies, and then I sing along quietly to my own playing, trying to drown out the thoughts of my own children whom I have left far behind me.

There is only Emre and his friend Markus in the Café Schubert when I arrive, and I make myself some coffee and sip it slowly whilst wandering around before playing. The place smells of bread and a strong exotic perfume, and is familiar to me as anywhere is in this town. It is a large place with rather artistic photographs on the walls, of what I assume is Istanbul, Islamic architecture, and turbaned men sat drinking coffee, playing chess or having earnest conversations about Allah. The café used to be a traditional bakery, but the owner died suddenly and there was no family to pass it onto, and then Emre appeared out of nowhere, lost but with money, and now the Café Schubert is as much a part of the town as the bakery ever was, and Emre is as trapped here as I am.

I sit down at the white piano in the corner and start to play an Impromptu by Schubert but Emre does not seem to notice. He looks so beautiful as he talks intently to his friend, speaking a mixture of German and Turkish, completely without self-consciousness whilst Markus smiles and looks over to me to give me a wink. Soon there are others arriving and Emre stands behind the counter, and the cafe becomes an amalgam of noise, of which my playing is just one element.

Markus comes and sits by me as I take a short break from playing. Markus is a carpenter and has a shop close by, but he seems to spend more time here helping out with drinks than he ever does making things. Emre is busy serving customers and Markus looks over at him fondly.

“Emre has done well with this café,” I venture, “not something you would perhaps expect in a small town like this.”

Markus smiles, “Even the most out of the way places change eventually, their tastes and what is acceptable. He had trouble getting customers at first, but people adjust.”

“To his being Turkish?”

“Well, that as well.”

He kisses me on the forehead and I go back to the piano, my brain mulling over what Markus had just said.

***************************************************************************

“You never talk of your children? When I was talking to Frau Kurzweg she did not even know that you had any.”

“Well they are far away, and I am trying to start again, no point in dwelling upon things.”

Grischa looks sad and puzzled.

“But how can you not talk about them? Not even try to ring them?”

I realise that I am crying, tears running down my face. I know that I have to stop this, so I quickly wipe my face and then take our empty plates from the dining room table and start to wash them, leaving Grischa uncomprehending and sad, until he joins me, and we put the crockery away into the heavy cupboards, and talk of other things.

I sit in the kitchen and drink some wine with Grischa besides me, and then we kiss, my mouth tasting of the wine and tears, and without a word he leads me up to his room and, watched by his grandmother’s oil paintings and photographs of various Victorian writers, we make love, the first time in weeks, and I fall asleep naked in his arms. But my dreams are horrendous and eventually wake me. I go downstairs and play some Mahler in the early morning sunlight, which streams through the large window and makes me forget everything, but that I am a lone woman playing the piano in a small German town thousands of miles from where I was conceived and born, and where I am doomed to stay.

There is a telephone box in the Stadtplaz and I ring the number I know so well. The telephone receiver feels damp and rather unpleasant and I wipe my hands on my sides. Far away in England I imagine the small green telephone on the coffee table vibrating slightly as it rings, but presumably it has been moved now, packed away and disposed of. The telephone continues to ring and then there is a click and I am relieved – the horror if somebody had replied. I see the empty rooms bereft of life, and I feel my eyes start to water again, but I am strong and wipe the stillborn tears away, leave the telephone box, find a bench and munch on chocolate.

It is still quite early but the town is beginning to wake. School children walk past me towards school and shops begin to open. Grischa drives to school so I won’t see him, but there are other people I start to recognise. If only I had met Grischa when I was younger. I concoct a fantasy of my studying music in Germany instead of London, meeting Grischa and his taking me home to his parents, and then a big, fancy wedding with all the townspeople there. If only one had these second chances.

And I remember Pete, sweeping me off my feet, introduced by a friend who was more concerned than me about my still being single. In retrospect, I think she was jealous that I was free and happy. The quick marriage in the registry office, Sam already beginning to show, and then to the house we couldn’t afford, Pete swiftly turning into a bad-tempered man without any fun or kindness in him and the two children gradually growing up the same. And me, trying to fight back but subsumed by them, until all I could do was make one bid for freedom before they completely devoured me.

I have an hour until I am due at the café and I walk around the town. On an impulse I start to walk out of the town, but then I realise that I have no idea where to go? Whichever road or path I walk down leads back into the town. As I walk I see two children, a boy and a girl only a little younger than Sam and Julie, and I smile at them hopefully, but they do not respond. Perhaps they recognise the darkness in my soul or think that I am a demon come to devour them. After giving up on leaving the town I walk towards the church, not knowing what has brought me there, as I try to avoid Holy places. Grischa occasionally goes there for baptisms and even for the odd Sunday service but I can barely bring myself to look at it, avoid the pastor and refuse to allow Grischa to invite him to dinner.

I wander through the graveyard looking for the graves of Grischa’s ancestors. His surname is Schulte and there are a few graves for people with that name, nothing too ostentatious, and many weathered well. Close to the fence that divides the graveyard from the house I see his parents’ graves: Pietre, who died ten years ago, and Elke, only last year, both relatively young. There are plenty of flowers, all looking fresh, to show that these people are still alive in the memory of the town, and many of my pupils still talk of them as if they are still alive or had just popped out for a ride down the road and will be back shortly.

Grischa finds me at the graveyard; he looks at me his face full of concern.

“Leigh?”

I look unseeingly at my watch, “I am sorry, I completely forgot the time, I had better get back to the café.”

“But it is evening.”

And I realise how dark it is and that I am cold. He gives me a coat and after a moment we walk home together, his arm around my shoulder.

“I got home and you weren’t there, and Herr Techeurt telephoned and told me that he saw you in the graveyard; he was very worried about you. He said that he stood and watched you, but you did not notice him.”

“I’m sorry, I was just thinking,” I tell him, feeling confused, and once we are back at the house I go straight to bed, where I sleep but do not remember my dreams.

The next morning we go for a drive. I have packed a picnic of bread and cheese, and even a bottle of wine, making me feel rather decadent.

“Are you sure you want to go out,” he asks me, obviously still concerned, “we can stay at home if you prefer, maybe play the piano and rest.”

“I am fine Grischa,” I say, “it will be lovely to get out.”

“There are some woods my parents used to take me to as a child. It is not far, just the other side of the town, but better to drive.”

As we set off I am aware of Grischa looking at me with concern, so to distract him (and myself) I ask him about his childhood.

“Did you have any brothers or sisters?”

“No, I would have liked someone, but my mother could not have any more after I was born; I almost died in the womb.”

We arrive at the woods, beautiful and refreshing, and we walk along, the sunlight finding us through the branches above our heads.

“What about you? Any brothers or sisters?” he asks.

“I had a sister, Anna, she was much younger than me.”

“You have never mentioned her before.”

I take his hand, “We never got on. She was very spoiled and came between my parents and me, and then she died, an accident. I do not think about her any more.”

“But she was your sister.”

I laughed, happy to be out in the woods with Grischa. The last thing that I wanted to do was think about the past.

We find some grass, which looks flat, and sit down to eat. I feed him sandwiches and cake as he lies with his head on my lap. I can feel his hair against my thighs through my linen dress. I stroke him. His face was almost smooth, with just the faintest hair on his cheeks. He becomes passionate and starts to kiss my thighs as I continue to stroke him and lie back on the grass.

“Why are you crying?” he asks. We both must have fallen asleep; it is mid-afternoon and the sun is still hot. I have woken from a disturbing dream to find myself naked in his arms. I wipe my face.

“What is wrong” he asks me gently.

“Can’t we leave Grischa?” I beg him, “just get in the car, and drive far away. I feel so trapped.”

He holds me, and kisses my forehead, “but I have school in the morning,” he tells me gently, “and this where I belong, and where you do too.”

“I don’t belong; it is not my town,” I tell him, “and I feel as if I have been caught.”

“Caught by whom?”

“I don’t know,” I tell him, and get up, putting my dress back on.

We reach home at about five that evening; Grischa had fallen back asleep and I too feel weary, so I sing Gilbert and Sullivan arias to keep me awake. I hear Grischa stir as we drive up to the house.

“Are we home?” he asks.

“You are.”

“There is someone at our door,” he says, surprised, and hurries out of the car to speak to the two English policemen who stand waiting for us. They stare at me as I sit watching them from behind the windscreen, and then they speak to Grischa in hushed tones, who still looks dazed and dishevelled.

I knew that they would come, had been waiting since leaving my house in Hounslow all those months ago, the last cries of my children fading away into the silence of the bloody house. Even Bredenbruch was not safe from the outside world.

Quickly I lock the car door, and as Grischa comes towards me, a look of horror on his face, I start the car and drive it straight towards him, trying to pick up as much speed as I can in the short distance between him and me. He is saying something to me, pleading, his eyes shiny with tears, but he refuses to move out of the way. The two policemen behind him grab their guns, but they are too slow, and Grischa falls in front of the car with a cry. I hear the crunch of his body as I drive over him.

I swiftly reverse and head out of the drive. One of the policeman fires but does not appear to have hit the car, and I leave them in my wake. I follow the small roads that surround the town, hoping to reach the autobahn, but for some reason I cannot find it. I have not left the town or its vicinity since arriving here and am now completely lost. I try to remember how we got here, when Grischa drove me here for the first time, but my mind is blank. How long ago was that? It seems forever. I can hear the autobahn, as I can from the house, but wherever I drive there are more small roads, and then in the distance there is the church steeple and the shops and, to my horror, I am coming once more into Bredenbruch.

I can see Emre, just walking out of the Café Schubert with a cigarette in his hand, looking handsome and calm. I pull over.

“Emre,” I cry and he looks over at me puzzled, but then Markus comes out of the café, and pats his arm and stands close, and they laugh about something.

“It is okay,” I say to myself, and give them both a wave as I speed off, thinking that the two men belonged in Bredenbruch much more than I ever had.

I drive forward once more, trying to find a way out, but every road I take seems to lead back to the town. I am panicking and so pull over to the side of the road and attempt to pull myself together. I eat some chocolate and after a few moments, feeling calmer, I start the engine again

I seem to have found a way out, as I drive for miles,

but still the autobahn remains a steady sound, close but just out of

reach. There are voices in my head, steady and calm, and I try to understand

what they say. And then I follow the road out through the woods, and

there is the church, stark against the sky. I find myself going down

the drive of the White House, where Grischa is standing waiting, his

arms wide to welcome me home.

Home