[an error occurred while processing this directive]

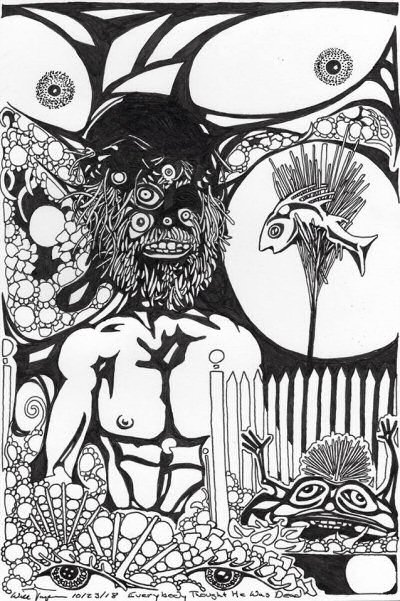

Artwork: Everybody Thought He Was Dead by Will Jacques

Venom and Leather

Darcy Lin Wood

The bus pulled away in a cloud of grey smoke revealing the teenage couple left beside the narrow road. Michael looked like the older one of the pair, due to his enormous size, but just like his girlfriend next to him, he was only 16. Nobody called him Michael though; everyone called him Mishka. His girlfriend, who at that moment was staring at a scrap of paper with instructions scrawled on it, was opposite in stature. At four-foot-tall she might have been confused for a child from a distance, especially as the top of her head only reached Mishka’s chin. Siobhan was her name, but fed up of mispronunciations and confusion over spelling, she went by the nickname Shrew.

Mishka looked down at his girlfriend’s stoic expression, as her massive backpack weighed down her little frame. There was always tenderness in his eyes whenever he looked at her, even when they argued. “I hope this retreat is nearby because this is literally where the bus turns around to go back again. Look.” He pointed.

The small empty bus trundled past, going in the opposite direction, and the driver gave the teenagers a disapproving glance.

“It’s a community,” Shrew explained for the umpteenth time. “A place where eco-warriors like us can live free from the constraints of society — away from our parents’ disapproval. Here we can be together and free.” She smiled and took Mishka’s hand in hers.

Every time she touched him, Mishka’s heart skipped

a beat. He looked down at her with her scruffy henna-red hair and big

brown eyes; Mishka knew he wasn’t really an eco warrior like her,

but he would follow Shrew to the ends of the earth.

“Come on then,” said Mishka. “We’ve made it

all the way up here into the Highlands, and I only have a tenner to

my name so we’d better find — what’s this “community”

called again?”

“Wild Haven,” replied Shrew, marching off in the middle of the road.

“Original,” muttered Mishka in tow.

The lane snaked ever upwards. Ancient trees and towering rock edifices loomed over the couple. No cars went by. Although Mishka would never admit it, as it got darker he was glad to feel tarmac under his trainers, reminding him that the remnants of civilisation existed even in the Scottish wilds. Under the trees it was fast becoming dark and despite being a veritable Goliath, Mishka felt unsettled.

It was pitch-black when the couple heard the faint sound of drums.

“What’s that?” asked Mishka.

“I reckon that’s Wild Haven,” Shrew squealed with delight.

Mishka saw the crescent of Shrew’s smile and felt her small hand pull him towards the sound. They jogged even though they were both tired from the long journey. Shrew weaved through tufts of blueberry bushes and sprang over tree roots, still with Mishka in tow. In her wake, twigs and branches flicked back into Mishka’s face. The white trunks of silver birches flashed passed as they ran.

At last they reached open ground on the brow of a hill and saw firelight below. Ahead of them was a valley that wended down to a black loch. On its sandy banks was a temporary settlement where people danced around several bonfires. It was summer and the starry sky reflected off the placid loch, which could have been a polished obsidian mirror. The mirthful revellers gathered on a stretch of beach between yurts and a log cabin; the dwellings only just discernible between firelight and starlight.

“Some of them are naked,” gasped Mishka.

“It’s an eco warrior community.” Shrew shrugged, sounding unmoved, although perhaps she wasn’t prepared for this show of sexual liberation. She and Mishka had had sex, but that was different — intimate and loving. Still she acted impassive, knowing that it had been her who convinced and then dragged Mishka off to find Wild Haven.

“Who’s there?” shouted a male voice.

They couldn’t see where the voice came from, but Shrew answered anyway, “I’m Shrew and this is Mishka. We’re here to join Wild Haven.”

“Then welcome. You have found it,” replied the disembodied voice. “Come, join us for some rabbit stew and try our concoctions.” The owner of the voice became visible as he stepped out from the trees near the pair. Mishka saw a sharp wooden spear in the man’s hand and that the man’s profile was a silhouette of mad curls. “I am Ox,” the stranger announced. “I will lead you down to our community where my partner – Raven – will welcome you properly, as I’m on lookout duty tonight.”

Ox led the teenagers down towards the merrymakers and as they came into the firelight, Mishka could make out Ox’s features; the hairy man was much older than them, bare-chested, and wore only a leather sarong around his waist. The hilt of a hunting knife protruded from a scabbard on his belt, and he used his spear as a walking stick. Ox was short, and his square stature suggested hidden strength.

The teenagers immediately knew, seeing the reveller’s wild unblinking eyes, that the dancers were intoxicated. The naked and the barely clothed, men and women alike, came forward in turn to kiss the newcomers. Shrew was ecstatic, but Mishka harboured reservations and didn’t know where to look as he was kissed repeatedly. However, being teenagers, they soon forgot their inhibitions. They took what Ox had referred to as the ‘concoctions’ handed to them in clay mugs by a dusky voluptuous woman called Raven.

Raven filled clay bowls of steaming rabbit and sorrel stew for them both. “Drink our concoctions, and eat our food and you will have taken part in the rite of passage to Wild Haven,” Raven explained.

“What’s in this “concoction?” asked Mishka before he would try the steamy malty liquid in his mug.

Shrew had already downed hers.

“This is a barley drink, but the crop had ergot –” Raven began.

“What’s that? Is it dangerous?” asked Mishka, looking at Shrew anxiously.

“Don’t worry young man,” chuckled Raven and took Shrew’s hand in both of hers, “I prepared it myself. It’s not dangerous, just a natural psychedelic, like LSD.”

“Don’t be a pussy,” Shrew snapped at Mishka, already slurring slightly.

Her cutting words sliced Mishka deep, and he downed his concoction.

A crescent of teeth glowed in the darkness as Raven smiled. By firelight Raven’s features were hard to see, except for her Cheshire cat grin and her dark eyes that reflected the flames.

“So Mishka – your name means bear in Russian, right?” Raven made small talk before the psychedelics kicked in.

“I think so. My granddad was Russian,” he replied without taking his eyes off Shrew.

“And Shrew,” Raven looked at the diminutive girl, “a resourceful and cunning little creature. Apt names I hope. We shall need a bear to help with fishing in the loch in the morning and a Shrew to work away at creating cloth. Perhaps we can even do some hunting –”

“But, I thought you were eco-warriors?” Mishka interrupted, having been expecting a commune of vegan hippies. Many of Shrew’s friends back home were of the eco-warrior ilk, and he had tried to fit in by becoming a vegetarian. However, after a week of grouchiness and a constant rumbling tummy, Shrew had begged him to eat a Big Mac.

“They aren’t vegetarian hippies,” blurted Shrew indignantly. “I told you they are eco-warriors who believe in living free from the shackles of modern society.”

“That’s an apt description,” Raven replied. “We believe that humans should move back into the natural world and coexist with each other and nature. We hunt, forage, fish and grow what we need as our ancestors did. We are trying to get back to basics and rekindle a sense of community. Also when the world does destroy itself, we will have forged the survival skills to persevere without government aid.”

The ergot-barley concoction started to take effect on the teenagers before they finished their stew. Their restless jaws chewed their lips and the insides their cheeks, until Raven handed them a ball of mint leaves each to chew on so they wouldn’t bite their mouths ragged. Raven remained by their side, watching over them, while explaining about Wild Haven’s bee keepers, tanners, miners, weavers, hunters, fishers and more traditional crafts that the teenagers hadn’t heard of. She also asked questions, particularly regarding whether anyone knew where the teenagers had gone.

“Of course not,” Shrew insisted proudly. “We wanted everyone to leave us alone so we came here secretly. We’re runaways.”

Raven was pleased and asked the teenagers to hand over their mobiles and any other devices that could connect them to the outside world and the drugged teenagers complied.

Mishka and Shrew’s pupils soon became black holes in their eye sockets. The world around them became a magical fantasy blurred with flame colours and drum beats. Naked flesh and shimmering starlight overwhelmed their senses as they became one with the world.

The next morning only fractured memories remained to Mishka and Shrew of the night before. Their bodies ached but, like all teenagers, they were able to brush aside the drug-induced hangover easily enough. They awoke in one of the yurts, lying on a bed of deer pelts. The embers of a fire glowed amber in the centre and above it, through circular hole in the low roof, the sky greyed before sunrise. As soon as they were dressed, Ox arrived at the yurt to take Mishka fishing.

By daylight, Mishka could finally see that Ox was an olive-skinned and broad-shouldered man with muscular arms and legs covered in dark fuzz. Ox looked at home in the wilderness, with his re-set broken nose and thick Neanderthal brow. Mishka guessed that Ox was in his mid-30s — more than twice Mishka’s age.

After Mishka had gone, Raven arrived and took Shrew to the wooden weaver’s hut. This solid-looking hut was the only permanent structure in Wild Haven, and it stood on stilts at the far end of the beach. Raven was roughly the same age as Ox, with muscular limbs and an hourglass figure. Her short black hair shone almost blue in the emerging sunlight. Raven had tanned skin and dark eyes surrounded by fine lines. She wore what Shrew assumed was a jute dress — sleeveless and dark. Little shells dangled from the hemline, clicking gently together as Raven walked.

“I like your dress. What’s it made from?” asked Shrew, in an attempt to make conversation.

Raven stopped and smiled. “This? You like it?”

Shrew nodded, eager to please.

“It’s woven from human hair.”

“Whose hair?” Shrew couldn’t keep her voice steady. The answer had perplexed her.

“Hair donated by the people of Wild Haven, as well as passers-by. Why not use what we can grow ourselves? Plus it’s a renewable source of material.” Raven shrugged and continued along the beach beside the loch. Shrew followed. Her eyes fixed on Raven’s dress.

The hut on stilts backed onto the forest behind. As the breeze changed direction the stench of rotting matter momentarily laced the air, then it was gone. Shrew noticed a deep pit beneath the building, right at the back. She could see white powder all around it.

At the steps up to the hut’s door, Raven turned to face the teenager as if sensing Shrew’s thoughts. “That’s a waste pit. We get some waste from hunting — especially when it comes to cleaning and tanning hides. It doesn’t normally smell, but it needs topping up with quicklime.”

The pair entered the first room in the hut. It was spartan, a small table being the only furniture. There was a huge loom at the centre of the room and a spinning wheel in the corner with a low stool behind it. The room was windowless, and both walls on either side of the entrance had shelves filled with bolts of cloth and yarns. On the far side of the room was the tannery door.

Raven wasted no time in showing Shrew how to work the spinning wheel. When Shrew looked apprehensive about touching the thread, Raven smiled warmly and assured the teenager that it was just wool.

“We get it from our own shepherds out in the meadows,” Raven explained. “The others are out gathering materials today, so it will just be you and me in here,” Raven said as she prepared to work the loom.

The two of them set to work without talking. It didn’t take long before Shrew was bored and starting to question whether coming to Wild Haven was a good idea. Her limbs ached from working on the spinning wheel and in all the scenarios she had imagined in running away with Mishka to Wild Haven, being driven like a slave had not been one of them. Soon a thrumming headache took her brain hostage. All Shrew wanted to do was sleep.

Raven finally stopped her loom and said, “It’s lunchtime. I’ll go and fetch us some food while you continue working. Don’t go through the tannery door as that’s where leather is curing and it has to remain at an even temperature. I won’t be long.”

Shrew nodded.

As soon as Raven had shut the door behind her, Shrew stopped the spinning wheel and sighed. Her leg was tired from pressing the pedal. Shrew wondered if the human hair of Raven’s dress had been made into thread on her spinning wheel. Raven’s dark dress shouldn’t have unnerved her like it did, but something about it bothered her. There was something unsettling about Wild Haven in general, but it had been her idea to run away to this community and she didn’t want to have doubts about it; her pride didn’t want her to be wrong.

“Perhaps if I take a peek behind the forbidden door it’ll ease my mind,” she joked to herself. She got up, gently stepping on the rough pine floorboards. Her super environmentally friendly biodegradable Puma InCycle sneakers gently pressed down the floorboards as she made her way to the tannery door without a sound. Shrew pressed her ear to the door and glanced around. The coast was clear. When she was sure she couldn’t hear the clicking shells of Raven’s dress, she pressed the door open.

As the door swung open the smell of salt and cedar oil immediately hit her nostrils. Inside were vats of brine with leather curing inside and pink scum floating on the surface. Wooden beams ran across the ceiling and from them leather hides hung to dry. To Shrew’s right was a desk upon which fox and rabbit furs were piled high.

The room met with Shrew’s expectations of a traditional tannery, and nothing seemed amiss. However, as Shrew examined her surroundings more thoroughly from the safety of the doorway, she could see long hair, in all different shades, hanging from a washing line at the back. It was more than just hair though. They looked like human scalps drying behind the leathers. As Shrew looked away, she also noticed a bright red cap and a leather wallet half-hidden underneath the pile of fox pelts on the table. In the floor, Shrew saw the outline of a trapdoor and knew the pit that she had noticed earlier was directly underneath.

The steps at the other door creaked, and the sound of clicking shells announced Raven’s return. Like a bullet, Shrew shot back to the spinning wheel and began pumping the pedal as if she had been working all along. Raven entered and noticed that Shrew was out of breath; she gave the teenager a lingering look.

“Everything alright?” asked Raven.

Shrew sensed her mentor’s suspicion and realised she must have given something away — perhaps it was the wild look in her eyes or the lingering scent of cedar oil that had seeped into the room. Shrew composed herself and prepared to lie. “I pricked my finger, and I hate the sight of my own blood.” She gave a smile that said she would cope.

Raven put down a wooden board with salted perch, gathered greens and cheese as well as freshly baked flatbread on it. “Let me see,” she insisted, walking towards Shrew with outstretched arms. Raven took Shrew’s wrists with a vice like grip before Shrew had the opportunity to make an excuse. Raven examined the girl’s hands.

All Shrew could do was pull her hands away. “It’s stopped bleeding now, don’t worry,” she said, feigning a smile.

***

It was a glorious summer evening when Mishka returned from fishing with Ox. Between them, they carried a barrel filled with water and live fish. The tannery workers had also returned, carrying a gutted stag across a pole ready for skinning. Others drifted in from the surrounding woodland, all of them carrying the spoils of the day, whether it was foraged greens or dead game. While the cooks butchered the meat and lit the fires, Shrew and Mishka headed into the cold water of the loch to clean themselves.

When they were treading water beyond earshot of the beach, the couple finally talked.

“Mishka,” Shrew began urgently, “even though I dragged you here, I think we have to leave — escape.”

“You think?” Mishka snapped back sarcastically. “Let me tell you what I saw today: I saw the hunters shoot that stag with a bow and arrow while Ox and me were fishing in a nearby stream. I saw the arrow pierce its neck. Then Ox explains to me that the creature wasn’t dead, just paralysed. I watched them gut the still living stag. I saw the whites of its terrified eyes from ten metres away and the hunters ripping its beating heart from its body. They use some kind of curare on their arrows — brewed by Raven out of mandrake, toxins found in ticks and adder venom. Ox says it keeps the meat fresh. What I’m trying to say is that for eco-warriors, these people are really fucking cruel,” he opined.

“What I have to tell you is even worse than that,” Shrew said quietly.

“I’m all ears,” replied Mishka, clearly still upset by what he had seen the hunters do.

Shrew struggled to get the words out. “I was in the weaving hut today, and Raven went to get us lunch. She told me not to look inside the tannery, but I looked anyway,” she admitted.

“Did she catch you?”

“No, but I think she’s suspicious. I said I cut my finger to explain why I looked flushed, but she grabbed my hands and checked and of course there was nothing there.”

“What did you see?” Mishka asked as he paddled closer to his girlfriend, his own upsets temporarily forgotten. He glanced nervously at the beach and the supposedly harmonious denizens of Wild Haven, before fixing his big grey eyes on Shrew again.

“At first I just saw leathers hanging and curing.” Shrew stalled.

“What did you see?” Mishka pressed her.

“I thought it looked normal for a tannery. But then, behind all that I’m sure I saw human scalps drying out – with long hair still attached–“

“Christ.”

“That’s not all,” Shrew continued, “I also saw belongings in there – a wallet and red baseball cap with a non-biodegradable plastic motif. It just doesn’t fit with these people.” She was beginning to shiver in the water but whether it was from cold or fear or both, she couldn’t be sure.

“Come on,” said Mishka. “We should be getting back. The last thing we want to do is arouse more suspicion, or catch pneumonia.”

“There’s more.” Shrew didn’t budge, even though Mishka had already swum one stroke back towards the beach. “At the back of the tannery there’s a trapdoor in the floor. Beneath it, underneath the hut, there’s a pit filled with quicklime. I think these people have been dumping carcasses in it. It sure isn’t a latrine. Around it, I saw rusty stains in the pine floorboards. I think they might be blood” – Shrew pursed her lips – “stains from human blood,” she said finally.

“What?” Mishka said with alarm, almost disappearing under the surface of the glassy water.

“Raven’s dress is made from human hair. At first I thought it was just jute, but she told me it’s human hair. No one here has short hair, except Raven. So where did they get it from? And the leathers — what if they’re not all from deer hides or whatever?”

Mishka was silent. He swallowed hard.

“We’re in danger,” Shrew said quietly. “I think Raven suspects I looked in the tannery. We have to sneak into the tannery, get that wallet and cap as evidence and then escape from here tonight. We’ll go straight to the police.”

“OK,” Mishka nodded and kissed Shrew on the cheek. “We’ll do it together, tonight, when everyone is asleep. Just don’t drink any of the concoctions they offer you at dinner,” he warned.

Shrew nodded, feeling safer now that she had told Mishka. The two teenagers paddled back to shore.

***

“Mishka?” Shrew whispered. “Are you awake?”

“Yeah. Couldn’t sleep anyway,” Mishka’s voice replied from the darkness. “Are you ready to go?”

“Yeah. You?”

“I’m ready.” Mishka leant over Shrew and kissed her. “Let’s go,” he uttered, struggling to keep his voice steady.

The couple slipped through the flap of their yurt as silently as ghosts. Around them, the night smothered all sounds. Heavy breathing and sleep murmurs arose through the cloth walls of the surrounding yurts, but nobody was awake outside. All the fires were in embers. A silver crescent moon looked like a thumbnail in the sky. The black loch was still and trees loomed over it against the star-smattered sky.

“This way,” whispered Shrew as she took Mishka’s hand to guide him.

When they reached the steps of the hut, the pair put their camping rucksacks down. Free of the weight they both ascended the steps silently. Shrew didn’t even pause in the loom room, but continued to the door of the mysterious tannery.

“In here,” Shrew whispered. She felt braver within the hut’s wooden walls.

“I’ll go first,” insisted Mishka and before Shrew could object, he had stepped around her and placed his hand on the door handle. He was determined to protect Shrew, whatever the cost to himself; he often thought of her as delicate and sometimes imagined that if she just tripped, then she might shatter like crystal.

Ever so gently, Mishka eased the handle down and pushed the door open. The cedar oil and brine smell seeped into the loom room. He looked around, but in the windowless tannery there was not a glimmer of light.

“Have you got a lighter, or a torch?” he whispered over his shoulder. “I can’t see a bloody thing.”

“Hang on.” Shrew felt around the many pockets of her loose cotton trousers, eventually pulling out a Zippo lighter; it had been a gift from Mishka on their first date. Engraved on the back of the Zippo were the words: You are my light in darkness. Shrew didn’t smoke, but was constantly breaking matches when she attempted to light incense sticks and candles in her room back at home. Realising this, Mishka had bought her the lighter. Shrew flicked the wheel down with her thumb, and there was a hiss before the flame took.

Mishka jumped. In the dim orange glow from the lighter he was face-to-face with the head of the stag that he had watched the malicious hunters butcher alive.

“What’s the matter?” whispered Shrew behind him, sensing her stolid boyfriend going rigid.

“Nothing. The stag’s head caught me off guard, that’s all,” he replied, feeling embarrassed by how jumpy he felt.

Shrew held the lighter up, and the pair of them began to look around the morbid little tannery. Mishka started by examining the cured leathers that hung drying from the rafters, while Shrew gazed into the vats of brine with a wrinkled nose.

“Shiiiit,” whispered Mishka.

“What?”

Mishka looked down at her. His eyes were wide with fear. “These hides here are leather from deer. But look at those two” —he pointed— “those two,” he hesitated again, “those two are human skin.”

With a trembling hand, Shrew held the lighter up to one of the hides. Sure enough, it was different. It was pinker and much thinner. More than that, the shape was human, minus a head. Ever so slowly, she ran the light from the Zippo along to the extremities and they both saw how the skin on the fingers had been delicately cut and peeled away in five rectangular strips. Shrew swallowed the hot sour bile rising in her throat.

Mishka made his way towards the back of the hut as delicately as a man of his size was able. Right at the back, hanging from meat hooks, were the human scalps that Shrew had mentioned. They all hung by their long hair, drying out. At the sight of this Mishka’s knees almost failed him. Adrenaline pumped through him as he realised the trouble that he had got himself and Shrew into by coming here. Their adventure was no longer about their parents catching them, but about preventing themselves from being skinned alive.

Shrew held her breath as she and Mishka heard footfalls mounting the steps to the loom room. The tannery door was closed, but Shrew knew who it was. The sound of shells gently clicking against each other drew closer.

“Quick, we have to get through the trapdoor. It’s the only way out,” she whispered to Mishka. “They must have spotted our bags outside by now,” she added.

The two teenagers dropped to their knees by the trapdoor, trying to find the means of opening it in the dark.

The footsteps in the loom room came to a standstill on the other side of the door. Shrew realised that she had not gathered the evidence, the cap and wallet, that they had come to retrieve. She chanced it and silently dashed to the table near the door. Mishka scrambled around the trapdoor and undid the bolts with trembling hands. The trapdoor made a loud creaking sound as it fell open, dangling downwards over the deep pit, from which emanated the smell of rotting flesh. Even in the dark the couple could see the pit as it was white with quicklime, which at close range did little to mask the smell.

Raven slammed into the tannery, her dark eyes blazing with anger. Mishka grabbed stunned Shrew in his arms and jumped backwards into the pit. Mishka took the full brunt of the long fall on his back, while Shrew in his arms was unscathed. Liquefied flesh smattered them both on impact.

The smell was repugnant, and both teenagers gasped for fresh air in the stinking hole. Mishka coughed and gagged, winded from the fall, while Shrew vomited as she rolled off him. The couple struggled to escape the pit as disembodied human hands clawed to keep them there. Underneath the teenagers, human and animal body parts snapped sickeningly as marrow-filled bones shattered under their weight. Splintering carcasses ripped their flesh as they struggled out of the pit.

“We have to get this quicklime off of us. It’s eating away at my eyes,” squealed Shrew, louder than she had intended, as they made it out of the pit.

“The loch!” Mishka grabbed Shrew’s hand

and pulled her towards the placid water. Mishka’s trainers were

just in the water when he felt Shrew tug on his arm; she became deadweight.

An arrow had gone through her bicep. He stooped to pick her up when

he heard the second arrow pierce the air. Before he had time to react,

the arrow pierced his lumbar. He fell to his knees with Shrew still

in his arms and instantly knew that the arrows were of the same kind

that the hunters had used to paralyse the stag without killing it. He

could feel the numbing poison spreading like ice through his huge body

as he collapsed, conscious but unable to move anything except his eyes.

Someone swung a cudgel at his temple and knocked him out. Neither of

the teenagers awoke as the denizens of Wild Haven washed the quicklime

from their skin and dragged them to the tannery.