[an error occurred while processing this directive]

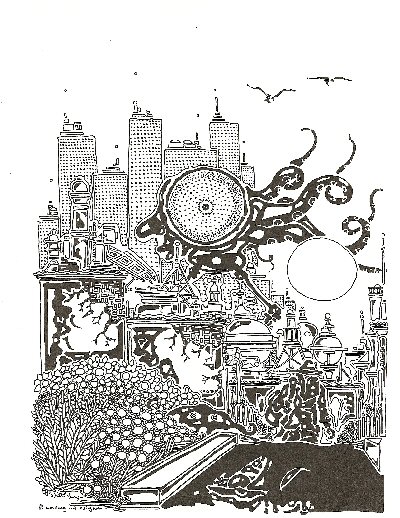

Artwork: Running at Night by Will Jacques

The Evolution of the Shambling Hordes: The Zombie from Mindless Servant

to Raging Revolutionary

Chun Lee

They are monsters come back from the unknown darkness of death with an unexplained intent to plague the living. Popular culture considers a zombie to be a near-mindless creature, craving the still-warm flesh of humans, not because they need it to sustain their undead existence, but because they have a single-minded instinct to consume. Zombies have always had difficulty earning the understanding of their audience. This is because their mindless nature makes identifying or characterizing with this classic movie monster a difficult task. Zombies are monsters without faces because there are very few individual zombies; not many of them even have the distinction having a name. There is no zombie Dracula to be a mouthpiece or face-man for these creatures. They speak in unison because a single zombie is not all too threatening. They are stumbling predators, easily avoided, and encumbered by their deteriorating bodies as much their simple mindedness. They do not scheme, they do not wait in the dark anticipating when we will be most vulnerable to them, ready to pounce on us when we are least expecting them. And the only strategy they seem to have is to come at their prey in mass numbers. In fact, it seems the only victims of zombies are those that are too terrified to react to them, or those that are too stupid to outsmart them.

Because of the inherent weaknesses in these creatures, they are only effective in large groups, behaving like a mob. With their rotting mobile bodies they remind us of our own mortality, but zombies also pull on a primitive string of fear, the fear of the mob. I argue that George Romero, who established the genre with his classic horror movie Night of the Living Dead (1968), and other filmmakers who try to reinvent the modern zombie, hit upon a primal fear of an aggressive collective, like a mob, revolt, or riot, which is seamlessly expressed through the modern cinematic zombie.

When I was twelve years old, an African-American man named Rodney King was beaten by four Los Angeles police officers. The beating was caught on tape and used to prosecute the police officers, but even though this assault on King was repeated on news shows for months, the four officers were acquitted of any wrongdoing. The verdict enraged the community of Los Angeles and what started as a protest against the verdict turned into a violent riot that lasted for several days, one of the worst in American history. Images of mob violence and anarchy have since been seared into my consciousness and an uneasy emotion arises within me whenever I see a zombie film in what Freud would call “that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar” (The Uncanny, pp. 369-370).

A riot represents a community in unrest. It is a mutual statement from its participants expressing anger, frustration, and a demand for change. In many ways, it is an entire group of people having a tantrum. This a unified statement presented with such conviction and volume that it can be given awe and respect.

“It is always inspiring when oppressed people rise up in fury. Rebellions such as this (Los Angeles riots) lift the cloak of propaganda and respectability that masks the naked horror of exploitation and murder, and let us see the rage and despair this oppression causes.” (Furr, p. 8)

If, as Furr suggests, a riot lets us see the pure “rage and despair” of an oppressed society, then what does it mean when filmmakers choose to use the imagery of a riot in a movie featuring zombies? Certainly there are connections to be made between the two. A zombie apocalypse involves countless numbers of the undead with the very single minded purpose to consume flesh and thus turn everyone else into zombies, while a riot is an entire community united by anger, wanting everyone to know and share in their discontent. Kim Paffenroth, writer of Gospel of the Living Dead, compares them to “a cult of Cannibalistic Shakers who must rely on “converting” others to their lifestyle in order to perpetuate themselves.” (p. 13) It is not simply the sheer amount of numbers out in the street that connect the two but the environment that they create. An entire community is reduced to the brutal laws of nature: consume or be consumed. Both a riot and a zombie apocalypse send a message through violence and the dismantling of social order. They also are a symptom of the need for social change, as Romero and other filmmakers often use the undead to make a statement about who we are.

It should be noted that though Romero intended to film a zombie movie every decade he was unable to get a film greenlit in the ’90s. Although Romero had a script written, he had great difficulty in getting any studio backing (Romero). It may be that seeing a mob of zombies would be imagery too sore and reminiscent of the civil unrest at that time and the connections between zombies and riots would be too easy to make.

The Servants

In order to accept the zombie as a revolutionary, we first have to

understand the origins of this layman of the movie monster universe.

Like many monsters, there is a root of truth that has been diluted

and replaced by legend and superstition. Zombies do exist. Maybe.

They certainly did exist. We must go to the island of Haiti

and understand the island’s culture to find for this particular

root of truth.

Haiti has the remarkable distinction of being the only country to have been formed after a slave revolt. It is a country with an incredibly unique origin. The native people of the Caribbean island were all but destroyed by European colonialism and so slaves from Africa were brought in to work in the growing sugar cane crops. These slaves, which were a hodgepodge of people from several tribes from the western side of the African continent, created a new religion, a mixture of Catholicism and African tribal religions, which we know as Voodoo. In this world of mysticism and superstition the zombie was born. The origin of the word zombie is just as much a convoluted and blending of cultures as the people of Haiti are.

Linguists have claimed that the etymological root of “zombie” might be derived from any (or all) of the following: the French ombres (shadows); the West Indian jumbie (ghost); the African Bonda zumbi; and Kongo nzambi (dead spirit). It may also have derived from the word zemis, a term used by Haiti’s indigenous Arawak Indians to describe the soul of a dead person. (Russell, p. 11)

Although there is confusion with the word’s origin there is no doubt of the mystical nature of the word zombie. Interestingly, the progenitors of the word zombie do not refer to an undead creature but a free or dead spirit. The confusion comes from the fact that Voodoo culture considers there to be two types of souls: the soul that controls the physical body and the soul that is the will of the person. As mysterious as the etymological origins of the word zombie are, they are not nearly as mysterious as the actual Haitian practice of raising the dead.

In the Voodoo-influenced Haitian culture it is not the zombie that is the true source of terror but the zombie master or witch doctor. In this island, Zombies are not the menacing creatures Hollywood has created. They are instead simple-minded servants that are usually used for menial labor, like working at a farm or sugar refinery. The true monster of voodoo myth is the zombie master. The zombie master creates and controls a zombie through the use of tradition, superstition, and a mysterious powder. When trying to understand the methods of a zombie master it is almost impossible to separate the myth from the facts. Luckily, there have been some attempts to scientifically explain this phenomenon.

Wade Davis’s Serpent and the Rainbow and Passage of Darkness offer a scientific explanation for the zombie myth. After traveling to Haiti to discover the secrets of the poison that is used for zombie creation, Wade finds that although the rituals and dominating powers of the witch doctor are perceived as the main reasons for zombies, the main active ingredient of the zombie powder they use is the poison found naturally in the poisonous blowfish. Wade finds that the purpose for zombies are as slaves to toil away for all of their existence. Their fate is enslavement. Yet given the availability of cheap labor, there would seem to be no economic incentive to create a force of indentured service. Rather, given the colonial history, the concept of enslavement implies that the peasant fears, and the zombie suffers a fate that is literally worse than death—the loss of physical liberty that is slavery, and the sacrifice of personal autonomy implied by the loss of identity (Davis, Serpent and the Rainbow, p. 138).

Davis comments about the scars of colonialism still with the people of Haiti, and it seems these scars even control their fears. It is not simply the fate of eternal servitude that is so troubling but that combined with the loss of identity and individuality, which may comment more about the psychology of slavery than any statistic. But the question arises of why these witch doctors were even allowed in this society. There is still a purpose for the Voodoo witch doctor, or the zombie master. Wade theorizes that the witch doctor is actually a necessity for Haitian society.

From extensive examination of the cases of Narcisse and other reputed

zombies, it did not appear that the threat of zombification was invoked

in either a criminal or a random way. Significantly, all of the reputed

zombies were pariahs within their communities at the time of their

demise. Moreover, the bokor who administers the spells and

powders commonly lives in the communities where the zombies are created.

Regardless of personal power, it is unlikely that a bokor who was

not supported by the community could continue to create zombies for

long, and for his personal gain, with impunity. A more plausible view

is that zombification is a social sanction administered by the bokor

in complicity with, and in the services of, the members of his community

(Wade, Passage of Darkness, pp. 9-10).

Davis argues that zombification, although a horrible fate, is used

as a punishment imparted by a society and not a bokor or witch doctor.

It seems that the witch doctor is a type of boogeyman to remind society

to keep from becoming “pariahs” to their society. This

phenomena eventually even reached the shores of the United States,

and stories of zombies spread until the concept became part of the

culture. When Hollywood searched for a new movie monster for a horror

film, it only had to look at its neighbors to the south.

Victor Halperin’s White Zombie (1932) is the first time the zombie becomes a cinematic monster. In many ways, this movie comes to represent colonialism’s hold on the small island nation of Haiti. The Zombie master of this movie is played by Bela Lugosi, a White man who stole the knowledge of zombie creation and used it against his own master. The plot of White Zombie is a classic story about obsession set in an exotic locale. A man and his fiancé, Neil Parker and Madeleine Short, plan to marry in the superstitious island of Haiti after an invitation from a rich land owner named Charles Beaumont. Beaumont’s true plans, however, are to win the heart of the beautiful Madeleine himself and marry her instead. Being a faithful young woman in love with her fiancé she refuses the advances of Beaumont (he makes his confession of love while walking the young bride down the aisle for her marriage with Neil Parker). With his advances shunned, Beaumont turns to the mysterious Voodoo master, Legrandre. The two formulate a diabolical plan to kill Madeleine and resurrect her as a zombie slave for Beaumont.

Madeleine is killed by poisoning and Legrandre raises her from the dead, but Beaumont realizes that a zombified Madeleine is not the same as the real thing. “She’s just not the same,” complains Beaumont. Legrandre and Beaumont argue over the fate of Madeleine and Legrandre kills his accomplice, using his hypnotic powers to dominate his mind. The movie comes to a climax with Neil Parker returning for Madeleine. Even though she is in his control, she refuses Lagrandre’s order to kill Neil. After a fight over a cliff in which several zombies and Legrande himself falls over to their doom, Madeleine returns to her senses never having really died, ending the movie with the appropriate Hollywood happy ending.

White Zombie introduces zombies for the movie-going audience and does a remarkable job at keeping to the Haitian myth. It presents them as servants and not malicious beings intent to do harm. In fact, these zombies do not kill by biting but by simple thuggish tactics like strangulation or by simply dumping someone into a well. There is no emotion in these creatures, although there is an eerie moment when Beaumont asks Legrandre what would happen if he ever lost control of his zombies. Legrandre responds by saying, “They would tear me to pieces,” instilling the possibility of an angry backlash from servants if they could only break free from the dominion of their master.

White Zombie is also a depiction of the plight of a nation trying to recover from the scars of colonialism. Instead of a Black man controlling the zombies we have a White man who is corrupted by the knowledge that these natives hold. A perfect metaphor of the grotesqueries of colonialism is Legrandre’s sugar mill. As the zombies drops armloads of sugar cane into a mill, a zombie stumbles into a vat of cane juice. Because they are nothing but mindless drones, no attempt is made to save their fallen comrade. Instead, the zombies continue working as the flesh of the zombie is ground and added to the sugar, a worker literally giving his flesh and body to the one and only goal, the production of sugar.

Racial divide is often a trigger for rioting, which is an issue that comes up a surprising amount in these movies. The fear of natives is consistent throughout the movie. Hollywood was even unable to procure a Black actor to play their necromancer, instead using Bela Lugosi, fresh from the success of his role as Dracula. The concept of a Black villain smart enough to outwit a White man from his wife may have been too explosive a subject to handle.

When Madeleine is kidnapped and it is suggested that she may be with the natives, Neil responds with: “Alive and in the hands of natives? Surely she would be better dead than that” (White Zombie). Considering that she was deemed to be dead a few days earlier, Neil’s reaction to the possibility of his wife’s resurrection and capture by natives seems contradictory to the loving husband. He would rather have her dead than alive and under the subjugation of the Black natives.

The Revolt

With a few exceptions, zombies continued to limp on through the years

with sub-par movies. Attempts to reinvent zombies as Nazis, pirates,

communists, and even space invaders resulted in only confusing what

type of monster a zombie really was. They may be creatures returning

from the dead but that was the only string between these varied movies.

Fortunately, this was soon to change, and the zombies gained a purpose:

they were given bite.

Genre-defining moments are few and far between for horror films, since filmmakers quite often prefer to churn out replicas of already established films. George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) not only reinvented the zombie as a movie monster, but changed the perception of what type of monster it was. Zombies never hungered for anything before Night. No one ever gave much thought to what undead things would want to eat. Giving them a hunger for flesh gives them a purpose, something they never had before, since they were always under the control of a zombie master. It is a simple, illogical purpose.

Strangely enough, it was not even Romero’s intention to refer

to his monsters as zombies. The title of the movie was originally

going to be called Night of the Flesh-Eaters and considered

his monsters as ghouls more than anything (Romero). The title was

changed by the producer, and the viewers all assumed that the flesh-eaters

were zombies. After the movie’s release, zombies never again

appeared as the mindless servants we saw in previous movies. They

now moved independently with their own purpose in mind; they craved

the flesh of human beings.

Night of the Living Dead begins with Barbara and her brother,

Johnny, visiting their father’s grave. Johnny teases Barbara,

telling her with uneasy foreshadowing that “they are coming

to get you, Barbara”. Johnny’s prediction does not take

long to prove correct, as the first of the undead assault the two

of them, resulting in Johnny’s death. Barbara escapes and runs

to a farmhouse, where she encounters Ben, another person seeking shelter

from zombie attack. Ben is a natural leader and takes control of the

situation, fights zombies, and barricades the house, while Barbara

falls into a catatonic state. They later find that there were several

people hiding in the basement of the house: a family of three, the

Coopers, and a young couple, Tom and Judy. As tensions rise between

Ben and Mr. Cooper over where they should stay to survive the night,

Ben once again reasserts dominance with a gun found in a closet. Mr.

Cooper is distressed because his daughter has been bitten by one of

the zombies and fallen ill. Cooper wants to hole up in the basement,

while Ben wants to defend the entire house. Ben and the group devise

a plan to escape their predicament, but the environment of indecision

and fear caused by the zombie menace results in the death of Tom and

Judy. Ben escapes back into the house, angry at Mr. Cooper for his

hesitation in letting Ben through the backdoor. The two fight over

the rifle, resulting in Mr. Cooper getting shot and escaping into

the basement. When the power goes out, the farm house falls into chaos,

and the undead come after the remaining survivors in full earnest.

Barbara is eaten alive by the zombies and Mrs. Cooper runs to the

basement to find her now undead daughter feeding on Mr. Cooper. She

then falls victim to her daughter in the film’s most graphic

death scene, a young girl repeatedly stabbing her mother with a pottery

shovel. Ben escapes into the basement, kills the young zombie, and

waits out the night as the zombies take the house above. The movie

ends with a gang of hunters and policemen restoring order by shooting

down zombies as if they were on a hunting trip. They clear out the

farm house of zombies, and when Ben comes out of the basement he is

ironically mistaken for a zombie and shot in the head by the posse.

Much has been said about the message of Night of the Living Dead. It is a movie suggesting that even in times of great risk and uncertainty, the true danger comes from one another. The film creates an atmosphere of lawlessness, where strength and the gun is the final word. We see Ben establishing his dominion over the house by claiming, “If I stay up here then I’m fighting for everything up here. You can be the boss down there. I’m boss up here. If you stay up here you take orders from me.” Ben’s dialogue is an example of how people revert to an almost primitive set of priorities in times of lawlessness and danger. Ben’s concern is not about his fellow housemates but in keeping what he feels is now his, fighting for every inch of a small farmhouse in the middle of nowhere.

Although Romero never considered Ben’s race when he was casting his movie, his decision to cast a Black man still screams out a message regarding race at the time of the film’s creation. The movie was filmed at a time when African-American male leads were never mixed with White actors. When Ben fights off White zombies in fine suits his aggression goes beyond a need to defend his life. He takes extra care to bash his opponent’s brains in and continues to attack even after his victims cease to move. Only in a movie featuring zombies could this scene be brought to life without inciting racist anger.

The greatest difference from the servant zombie to the ghouls in this movie was that although their motives were simple, these creatures were not under the control of a zombie master. Although the zombies now have independence, they are unable to succeed with their revolution to take over the world. At the end of the movie a posse of police and redneck hunters reestablish order by shooting the dead, but this is not the secure order that we might expect. It is misguided, enjoying reestablishing order as if it were a hunt. The final irony of this order is the accidental shooting of Ben. Unable to see the difference between a zombie and a human, they kill the only person who seemed to have a clear head on his shoulders throughout the movie. To add insult to injury, they treat Ben’s corpse like a side of beef, using meat hooks to move his carcass to the fire. Order is restored but we are suddenly left to wonder if this order was any better than the chaos of the night of zombies.

We must also consider one of the major inspirations for Night of the Living Dead when we wish to examine the revolutionary message in the movie. Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (1954) is a novel about the last man on Earth after a vampire apocalypse. Robert Neville searches for an explanation to a vampire virus to which he is immune, but has infected or killed everyone on the planet, and while searching he also has a battle against loneliness and madness taking control of him. Robert eventually finds his answer but is surprised to find that some vampires have retained reason and are even beginning to recreate human society. But because Robert is now considered the monster, killing vampires during the daylight as they sleep, the vampires decide to execute him. Robert realizes that he is no longer a part of this new world, and the final thought to run through his head as they take him to be executed is the title of the book: I am legend.

It’s easy to make connections between Night of the Living Dead and I Am Legend. In both stories we see a need to barricade and insulate oneself from a changing and hostile world. Robert represents the last of the old world, desperately trying to hold onto his humanity. This can only be considered as revolutionary. In I Am Legend, the changing world is directly compared to a revolution.

“New Societies are always primitive,” she answered. “You should know that. In a way we’re like a revolutionary group—repossessing society by violence. It’s inevitable.” (Matheson, p. 166)

Like I Am Legend, the violence of the zombies in Romero’s film is excused as “inevitable”, and certainly revolutionary violence can be considered cannibalistic. Revolutions often require one society to swallow up the other, so it only seems natural that Romero’s revolutionaries eat the living.

“It’s just something that’s happening, it’s just a different deal, it’s a different way of life. If you want to look at it as a revolution, a new society coming in and devouring the old, however you want to look at it” (Romero, ‘The Film Journal Interview’).

Here Romero describes the undead phenomenon as “something that’s happening”. It could be considered to be like a storm or other natural disaster that creates an environment for greater examination of the human condition. Stressful situations and lawlessness can oftentimes create a microcosm of a nihilist world.

A Revolution in Full

Although a twisted reflection of order is reestablished in Night

of the Living Dead, the revolution is in full swing in Romero’s

sequels: Dawn of the Dead (1978), Day of the Dead

(1985), and Land of the Dead (2005). Dawn is the

story of a few people who escape from the revolution and find temporary

refuge in a large mall in Pennsylvania. The movie’s main message

is about the excesses of American culture and the separation of haves

and have-nots. After securing the mall, the four survivors enjoy all

the goods within it and try to live a life of materialistic happiness.

Romero does a fantastic job of showing just how hollow this kind of

living is. Shopping and gathering can only mean so much in a world

without order. When Steve proposes to Fran with a ring he found in

the jewelry store she refuses, saying, “It wouldn’t be

real.”

Eventually a ragtag group of survivors reminiscent of a motorcycle gang of Hell’s Angels finds the mall and accuses our heroes of “not sharing”. The gang breaks into the mall, also letting in the horde of zombies that have been patiently waiting to get in. Our heroes have the option to hide in the mall and wait the gang out as they loot the stores and even jewel-wearing zombies, but they insist on defending their goods: “It’s ours, we took it!” This irrational decision results in Steve’s death and the loss of the mall. Romero uses this as a message to suggest that the mall, a metaphor for consumerist culture, belongs to the zombies. The final montage of the movie is a series of zombies reclaiming the mall and “shopping”. They are the only ones who can truly shop as much as consumerist culture would suggest and, of course, never drop.

Day of the Dead features a world fallen to the control of zombies. The movie is set in an underground military base occupied with the last remnants of human society. Unfortunately, as in Night, tensions are at a palpable high in the bunker. Soldiers control the bunker through force and demand scientists try to find a secret weapon to destroy the zombie menace. But the main scientist, Dr. Logan, has long ago given up on creating some type of superweapon. Instead, he spends most of his time and effort on befriending a zombie named Bub. Logan’s intentions are to domesticate the zombie and somehow make him a servant. Logan gets some surprising results with his star pupil, Bub. Showing signs he can even learn to use simple devices, Bub does not see the doctor as food and even recognizes him as a friend. Before this movie, Romero would blur the lines between zombies and humans by showing how much a human is like a zombie, but in this movie he showcases the zombie’s ability to mimic a human. He also offers the delusion of somehow gaining control of the zombie, taking this movie back to the origins of the creature, when it started out as a mindless servant. Unfortunately, this is not only hopeless in a world where humans are so drastically outnumbered by zombies, but ridiculous to think anyone would tolerate being in such close quarters with a moving, rotting corpse.

Romero’s zombie movie, Land of the Dead, offers an extension of themes that began in Dawn and Day. In both Land and Dawn we have an elitist society playing blind to the zombie apocalypse, instead trying to live in a hollow excess. In Land the zombie evolution continues with the zombie known as Big Daddy. While Bub was able to learn simple tricks and later on gain a simple concept of vengeance, Big Daddy is able to handle a complex rifle and can equate human raids to be from human civilization across the river. He also shows a characteristic that no other zombie had before: he can lead and teach. With Land, the revolution finally has a leader, and Big Daddy leading his zombies to walk through rivers, teaching them how to use tools, and even giving them basic strategies of attack. Big Daddy becomes a leader with whom we can even sympathize. All of his actions are for the betterment his own people and he is willing to make sacrifices and take risks for those people. Certainly there is no such leadership in the human encampment and it’s easy to cheer for their downfall.

The Revolution Spreading

We depart from Romero’s films to take a look at other directors’

interpretations of a zombie revolution. In Dan O’Bannon’s

Return of the Living Dead we see a different type of zombie.

These zombies move with more speed and are resilient to any type of

death; even damaging the brain seems to have no effect on these zombies.

Although zombie movie fans tend to dismiss this movie as a simple

tongue-in-cheek splatterfest, this movie does add at least one element

to the zombie culture that has since stuck: a craving for brains.

There may be more reason than simple gore to explain the appetite

for this particular cranial organ. Annalee Newitz argues in Pretend

We’re Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture

that the brain is a sign of economic rigor (p. 46). If intelligence

and the organ related to intelligence, the brain, is related to wealth,

then we can conclude that the zombies’ craving for brains is

in fact a need to gain wealth. Calling out for brains can then be

inferred to be a call for economic advancement, a common cause for

revolution and rioting.

The final film we can look at is 28 Days Later, directed

by Danny Boyle. Boyle’s film centers on an apocalypse created

by a virus known as the Rage virus. The movie’s opening sequence

is a montage of rioting and anger. We later see that the infected

monkeys were forced to view these images of human disharmony, implying

that the origin of the virus comes was human and our instinct for

anarchy transferred into an animal. The Rage virus does exactly what

its name implies—it takes over a person’s mind and infuses

them with nothing but an animalistic urge for violence. Since the

virus spreads through bites and the mixing of blood, adding in this

aggressive behavior creates a combination of circumstances that ensures

a near-instant spread of the virus on a macroscopic level. Although

these victims are not actually zombies (an injury that would kill

a human will kill a Rage-infected person), they share such similar

traits, mainly the loss of high reasoning and the ability to transmit

their state, that most viewers consider this to be a zombie film.

28 Days Later’s message stems from a mistrust of government

organizations. The movie starts with the highly immoral act of experimenting

on animals with viruses from an unnamed scientific organization. After

the apocalypse and the rampant spread of the virus, the few survivors

try to find refuge, hoping that there is some semblance of a government

out there to rescue them. When main character, Jim, and a small gang

of survivors finally find the remains of the military, they think

they finally have refuge from the Rage virus. Boyle uses an old theme

that is common in zombie movies: the threat from each other is still

greater than the threat from the zombies. Jim’s two female friends,

Hannah and Selena, are taken to be used as comfort women for the soldiers,

and Jim is taken into the forest to be killed. Boyle takes another

Romero-established theme, the concept that we are them and they are

us, to another level when Jim escapes his execution and releases infected

humans into the mansion in which the soldiers live. Jim takes advantage

of the fear and confusion, a micro riot, created by the release of

the infected people to rescue Selena and Hannah. Boyle does a fantastic

job of making Jim look like one of the infected in this scene, suggesting

that by joining the revolutionaries Jim is able to defeat his government

oppressors and save his friends from rape.

Conclusion

The future of zombie films seems to be currently murky. Even recent

critically acclaimed zombie projects like Shaun of the Dead,

the Dawn of the Dead remake, and the graphic novel The

Walking Dead tend to follow the same formula established in Night:

the survivors hole up somewhere they feel is secure, and a microcosm

for the world is created until the zombies reclaim the fortification,

scattering the survivors, with many people succumbing to zombie attack.

Whether the genre can be redefined now or in 50 years, the resilience

of the zombie genre is not in question. Although they are slow, creeping,

near-mindless monsters, the zombies are surprisingly quite successful

compared to any other movie monster. While the vampire is often burnt

by sunlight, the werewolf dispatched by a silver bullet, the zombie

hoards very often take over the world, killing most of humanity. They

establish a new world order and dismantle the old. Even the production

methods of these movies lend them to come from the small independent

film companies, since zombie movies are notorious for being made on

the cheap. No special effects are needed beyond some white power,

some fake blood, and sometimes generous amounts of clay. This makes

zombie movies much like the very monsters they feature: destined to

rise up again and again.

Works Cited

Davis, Wade (1988) Passage of Darkness (Chapel Hill and London:

The University of North Carolina Press).

Davis, Wade (1985) The Serpent and the Rainbow (New York: Simon and Schuster).

Freud, Sigmund (1934) ‘The Uncanny’, Collected Papers of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 4 (London: Hogarth Press), pp. 369-370.

Furr, Grover (2007) ‘Welcome the Rebellions!’, Canadian

Dimension, Jul 92, Vol. 26, Issue 5, p. 8.

‘George Romero at Comic-Con 2007’, YouTube, 11 Oct. 2007,

http://youtube.com/watch?v=jGdJtSs9CwE&mode=related&search=>

Kirkman, Robert and Moore, Tony (2005) The Walking Dead (Berkeley: Image Comics).

Matheson, Richard (1954) I Am Legend (New York: Tom Doherty

Associates, INC).

Newitz, Annalee (2006) Pretend We're Dead: Capitalist Monsters

in American Pop Culture (Durham: Duke University Press).

Paffenroth, Kim (2006) Gospel of the Living Dead (Waco: Baylor University Press).

Romero, George A. (2007) Interview with Rick Curnutte, The Film Journal, 11 Oct. 2007, http://www.thefilmjournal.com/issue10/romero.html>

Russell, Jamie (2005) Book of the Dead (Surrey: FAB P).

Filmography

28 Days Later (2002) Dir. Danny Boyle.

Dawn of the Dead (1978) Dir. George A. Romero, DVD.

Dawn of the Dead (2004) Dir. Zack Snyder, Perf. Sarah Polley, Ving Rhames.

Day of the Dead (1985) Dir. George A. Romero, DVD.

Land of the Dead (2005) Dir. George A. Romero.

Night of the Living Dead (1968) Dir. George A. Romero, Perf. Duane Jones, DVD.

The Return of the Living Dead (1984) Dir. Dan O'Bannon, DVD.

White Zombie (1932) Dir. Victor Halperin, Perf. Bela Lugosi, DVD.