[an error occurred while processing this directive]

He Said, She Said: A Survey of Men and Women’s

Views of the Genre and Its Sex Roles

Anthony J. Fonseca

I. Traitors to the Cause?

In a 2002 Femspec movie review, Kathleen Kendall reported discovering,

or I should say rediscovering, an interesting set of phenomena. First,

she, like feminist film critics Carol Clover, Isabel Cristina Pinedo

and Cynthia Freeland, had to ‘admit to having a guilty conscience

in taking pleasure from viewing [horror] films regarded as both violent

and misogynistic.’ As she states it, she ‘… felt a

“traitor to the cause”’ (82). In addition, Kendall,

after interviewing six young women who were both connoisseurs and amateur

producers of horror film, unexpectedly found herself raising the same

questions as Pinedo in her groundbreaking study Recreational Terror

(1997). Pinedo had argued that the assumption that the horror audience

is composed typically of adolescent males was one based on no hard evidence,

nor on any scientific studies (qtd. in Kendall, 82). Kendall found herself

reaching the same conclusion – that perhaps women willingly

made up a good bit of the horror audience, that they were all involved

in a kind of mass treachery, if you will. One possible reason for what

on the surface looks like a betrayal to the feminist cause is posited

by Jonathan Markovitz in ‘Female Paranoia as Survival Skill’,

his discussion of the role of paranoia in the determination of the final

girl (to use Clover’s term) in A Nightmare on Elm Street.

In this Quarterly Review of Film and Video study from 2000,

Markovitz points out that ‘while it is clear that horror films

contain representations of misogyny, it is a mistake to automatically

assume that they endorse misogynistic acts…. horror films might

actually expose misogyny as misogyny, and in the process provide important

critiques of existing power relationships’ (211). Or one other

possibility rests on a logical extrapolation of Pinedo’s theory

that no credible science validates the long standing belief that horror

is created by men, for men. In this article, I will present the preliminary

results of a double blind survey which I created to test the accuracy

of Pinedo’s theory. My intention was to collect concrete evidence

to either support or refute her calling into question the traditional

belief about the maleness of horror audiences, possibly exposing a large

fissure in the fundamentally weak base of the assumption that horror

is indeed a genre that appeals mainly to men. While it might be a difficult

pill to swallow, it is possible that scholars of horror fiction and

film may have been labouring under a false impression. This possibility

should hardly be surprising, given that a 1993 Publishers’

Weekly demographics report by Robert K. J. Killheffer verified

what an often cited 1980s Gallup study uncovered – that there

are at least two dominant segments in the horror literature and film

audience, young males and older, usually educated females.(1)

Such information serves to emphasise what have to be the biggest holes in horror scholarship. While many volumes exist which are informed by psychological theory, or sociological theory, or even film theory for that matter, glaringly missing from the literature are quantitative analyses that actually attempt to measure factors such as audience numbers, audience demographics, and in some cases, the acts of violence occurring on the screen itself. Though these studies would fall under what most scholars would term as ‘the dirty work’, they can be invaluable, for they are either the best proof of, or the best refutation of, our impressions or assumptions about the appeal and the audience of the genre. Unfortunately, only a handful of scholarly quantitative studies exist, usually found not in the literature journals, but rather in the media studies or psychology literature. One of the most intriguing of these is Fred Molitor and Barry S. Sapolsky’s content analysis-based ‘Sex, Violence, and Victimization in Slasher Films’, published in 1993 in The Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media. The two began by examining the validity of a 1980 Siskel and Ebert Sneak Previews idea, the so-called ‘women-in-danger’ film. Basically, what Siskel and Ebert were reacting to, and warning against, was what Linda Williams noted a decade later in Film Quarterly, where she argued that ‘the bodies of women figured on the screen have functioned traditionally as the primary embodiments of pleasure, fear, and pain’ for the horror, pornography and chick-flick genres (4). Almost concurrently, Clover’s Men, Women, and Chainsaws (1992) echoed that sentiment, with the statement that the victim in a slasher is ‘most often and most conspicuously girl’ (33). Molitor and Sapolsky revealed that women were indeed not the most often victimised sex in most horror film deaths, going against the grain by challenging what they viewed to be an incorrect perception too often masqueraded as fact.

II. WWJK (Who Would Jason Kill?)

In their 1993 article, the two took their cue from an earlier analysis

by Cowan and O'Brien (1990), which revealed no difference in the overall

number of male and female victims in 56 slasher films (233-34). Molitor

and Sapolsky continued the work of Cowan and O’Brien with a study

of 30 slasher films of the 1980s, chosen for their sales status, and

found two interesting truths: men were more often victims than women

(56 per cent to 44 per cent), and women were more often seen through

the subjective lens of the camera, in other words, from the killer’s

point of view. By the same token, women had more ‘screaming’

screen time (233-34). A follow-up article published a decade later in

Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, co-authored with

Sarah Luque, noted that both the number of female victims (down to 39

per cent) and the ‘scream time’ for women had dwindled by

the 1990s, partially in response to criticism (34-35). These studies

became a bone of contention between the authors and the research team

of Daniel Linz and Edward Donnerstein, the battle lines being drawn

in the pages of The Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media.

The central question was whether the genre should be analysed in isolation,

or compared to another genre, like action adventure. The Molitor/Sapolsky/Luque

findings validated the 1994 reply by Molitor and Sapolsky that seemed

to end all dissent. The significance of these results is clear: all

along, the impression that more women died during horror than did men

was simply that, an impression, and it was not one that could be proved

with empirical evidence. In fact, it was too easy to disprove.

Studies of a different type, more of a qualitative nature, arrived at similar earth-shattering conclusions. These include Brigid Cherry’s 1999 ‘Refusing to Refuse to Look’, in the collection Identifying Hollywood’s Audiences (1999), as well as Justin M. Nolan and Gary W. Ryan’s ‘Fear and Loathing at the Cineplex’, published in 2000 in the journal Sex Roles. Cherry’s survey of women indicates that they had a more complex range of emotions towards horror film than had previously been assumed, and that certain subgenres of horror hold sexual fascination for them (Barker 329-30). After conducting surveys and interviews with men and women who had watched horror films, Nolan and Ryan found that there was little difference in the way either sex reacted, with the exception that men had more frustration mixed in with their fear (Barker 322-24). Yet another benchmark publication, Pinedo’s 1997 text based on her personal viewing of some 600 films, is valuable for her theory of the shifting gender role identification possibilities for viewers. The relative strengths and limitations of these particular studies are reviewed by Martin Barker in the September 2003 issue of the European Journal of Communication. The most promising biologically based qualitative study seems to be Richard Jackson Harris’s, published in Media Psychology in 2000. In ‘Young Men’s and Women’s Different Autobiographical Memories of the Experience of Seeing Frightening Movies on a Date’, Harris concludes that as far as the selection of a horror film was concerned, ‘when the movie was selected by an individual [and not by that person’s date], there were no significant sex differences, indicating that males and females were equally responsible for choosing the film’ (253), and that ‘sensation seeking’ did not play a major role in horror’s appeal (262). The main sex difference Harris notes has to do with reaction to the film, for women ‘looked away a lot or left the room and returned a lot’, much more often than did men, the rates being 31 per cent for women to 7 per cent for men (253). Other reports that place biological sex differences at the centre of the horror debate usually deal with female children. Michael Wilson’s ‘The Point of Horror: The Relationship Between Teenage Popular Horror Fiction and the Oral Repertoire’, in Children’s Literature in Education (2000), looks at the commercial success of the Point Horror series in England (known as the Chillers series in the United States), arguing that horror helped ‘to exorcise the fears of the adult world’ (3) for teens, similar to horrifying oral folklore. Wilson notes no difference whatsoever based on the sex of the reader. And finally, Deborah Hicks and Tami K. Dolan in a 2003 issue of Changing English report a case study wherein the two discovered that four teen girls from at-risk cultures adopted horror as the best metaphor for their own experiences with violence, that the girls were ‘constructing their own counter-culture literary discourse’ (54). The unifying principle behind these qualitative and quantitative studies seems to be that we can no longer assume that men make up the bulk of the horror audience, or that women view horror only as an act of politeness on a date or for the benefit of a partner. They also call into question audience reactions.

III. The Survey Says…

I set out to fill some of the gaps in horror readership and viewership

studies by creating, with the help of the online surveying tool Survey

Monkey, a double blind modified snowball survey. My intention was to

attempt an answer at a few questions:

• Is the horror audience mainly male?

• Do men and women view horror differently, and is there a difference

between the sexes when it comes to a preference for filmed horror over

literary?

• Do both sexes recognise the apparent evolution of sex roles

in the genre, and if so, what are their impressions?

My methodology was simple: once the survey was created, I disseminated

it by sending it to approximately 30 colleagues. Half of those came

from the library in which I work; the other half was comprised of instructors,

professors and librarians from other institutions. I asked these people

to take the survey if they so chose, and then to begin passing it along

to their friends, colleagues and students. I gave little more instruction

than this, other than to state that the information would remain anonymous

and that ‘a colleague’ would use the information for a presentation

on horror and gender. I kept questions as vague as possible, and did

not ask about film or the role of women in horror until the latter half

of the survey, as I did not want to tip my hand, in an effort to avoid

having respondents play to the intention of the surveyor. I kept the

survey double blind by revealing nothing about myself, and by not asking

for specific identification information from any respondents.

Early questions simply asked about biological sex, gender identification and sexual preference, as well as age.(2) About five questions into the survey, I bluntly asked the respondent whether or not he/she considered himself or herself a horror fan. The choices allowed for a Yes or No response, but also allowed for respondents to choose to continue or discontinue the survey. I did so for three reasons. First, I did not want results to be skewed by someone who simply wanted to rush through. Second, I did not want to rely solely on the participant’s self-proclamation of fandom, since such a definition is arbitrary. Third, I did not want to predetermine the survey results by limiting myself to only a certain group of individuals – self-proclaimed horror fans. This was not to pose any problems in the analysis stage, since it is easy to isolate the responses of self-proclaimed fans and non-fans, making comparison simple as well. I also loaded questions which asked for respondents to choose favourites among authors and films, with choices that reflected the types of gender roles associated with horror. In other words, I purposefully listed some films with active heroines, some with passive leads who need to be saved, and some with seemingly passive leads who fight when cornered. Rather than ask respondents to choose one, in each list I asked for three choices, to avoid the obvious responses of King and Rice for favorite author(3), and to prevent respondents from having to chose one ‘favourite’ film. Finally, I peppered a few open ended questions into the survey, to allow for possibilities which I did not foresee. My hypothesis was simple: if men and women were indeed aware and appreciative of the changing sex roles in horror, the authors and movies they cited as favourites would unconsciously reflect this.

The survey was administered automatically as a live link for six months, after which time I had 310 anonymous respondents. Since I consider this to be a work in progress, I will continue to keep the survey live and available for another three or four months.

IV. He Said, She Said

To deal with the issues of sex and gender identification, the survey

asked two questions. The first was a straightforward ‘Are you

male or female?’ inquiry, but a note was added to indicate that

the question addressed the participant’s biological sex, not his

or her identification with the male or female sex, which respondents

were told would be asked later. Of the 310 respondents, 88, or 28.4

per cent, indicated that they were male. Two-hundred and twenty-two,

or 71.6 per cent, indicated that they were female. This result may seem

surprising, given the acceptance that horror is generally written for

males, but there are two phenomena at work that may explain the preponderance

of women over men as respondents. Since no attempt was made to dissuade

people from disseminating the survey link to members of their own sex,

the roughly seven to three female to male ratio could have resulted

because the first tier contacts made in this modified snowball study

were predominantly female. In addition, survey literature points out

that men are often underrepresented in surveys since they have a tendency

to avoid taking surveys, whereas women are much more cooperative about

taking them.

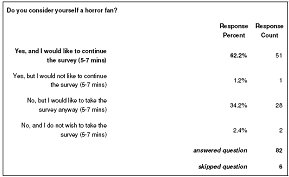

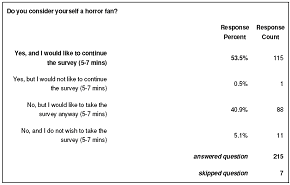

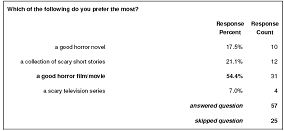

Of the 82 male respondents who answered the question, do you consider yourself a horror fan, 52, or 63.4 per cent, answered YES. In comparison, of the 215 female respondents who answered the same question, 116, or 54 per cent, stated that they were horror fans (see Figure 1). These numbers were unaffected by the age of the respondents, although younger females were more apt to not classify themselves as horror fans. Women between 25 and 40 were least likely to identify themselves as fans, with only 51.4 per cent answering YES. My results mirror those of the Gallup poll, for the female respondents most likely to identify themselves as horror fans were in the 41 to 55 age range (58 per cent answered YES). The responses to this question from men were similar to that of women in that the age group least likely to identify itself as horror fans was the 18 to 24 range. Only 44.4 per cent were self-professed fans. The age range most likely to identify itself with horror fans was the 25 to 40 group. Seventy-three percent of those respondents answered YES to this question. No one under the age of 18 was included in the survey. These results indicate that men are much more likely to claim to be fans of the genre. Another interesting finding is that age plays a much larger factor with men than with women, with a 20 to 30 percentage point differential in age ranges. While only 51.7 per cent of men age 41 to 55 answered YES to the question, 71.4 per cent of men in the 56 to 75 age range did likewise.

Figure 1: Male Respondents (Top) Compared to Female Respondents

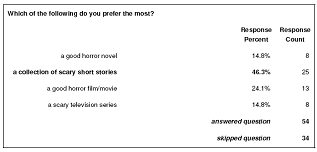

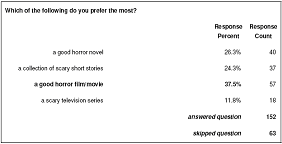

Both those women who identified themselves as not being horror fans and those who were self-professed fans identified King, Rice, Crichton, Koontz and Poppy Z. Brite as their favourite novelists. When asked to identify three favourites, King was listed by 72.9 per cent of female respondents, followed by Rice with 55 per cent, Crichton with 35.1 per cent, Koontz with 33.8 per cent, and Brite with 19.9 per cent . Female respondents ranked Poe, King and Lovecraft, respectively, as their favourite short story authors in the genre. There was almost no difference in preferences between self-professed female fans and female non-fans, despite the predictable predisposition towards short story collections for non-fans (see Figure 2). While female fans identified horror films as their favourite format in the genre (46.3 per cent), non-fans were equally adamant about collections and anthologies being their favourite formats (46.3 per cent). Fans stated they much preferred movies and novels (a total of 78.9 per cent) over short stories and television, as opposed to non-fans.

Figure 2: Female Non-Fans (Top) Compared to Female Self-Professed Fans

When it came to favourite novelists, there was little difference between male and female respondents. Men preferred King (71.9 per cent), Rice (49.1 per cent), Crichton (43.9 per cent ), Koontz (26.3 per cent), Brite (12.3 per cent ) and Ramsey Campbell (12.3 per cent). The major differences between the sexes here are that men rated the science fiction-based horror of Crichton much more highly over the traditional horror of Koontz than did women, and men included Campbell among their top authors. Men also ranked Poe, Lovecraft and King, in that order, as their three top short horror fiction writers. Both sexes seemed to prefer the standards to new voices, especially those writers known for their female leads. Neither Kelly Armstrong, Tananarive Due, Jemiah Jefferson, Billie Sue Mosiman, Caitlin R. Kiernan, nor Nancy Kilpatrick did well with women; Armstrong fared the best of these women at 7.3 per cent, and there was no difference between the number of fans versus the number of non-fans who identified her as a favourite. Men responded along the same lines, with Due managing to achieve the highest percentage of votes, at 3.5 per cent. This was unchanged whether or not men identified themselves as fans.

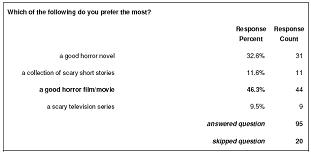

When it came to the preference of film to literary horror, men and women again showed striking differences. Overall, men ranked the two visual media, movies and television, over the two literary media, novels and short fiction, by a total of 61.4 per cent to 38.6 per cent. Women did not show a preference for video media over literary; only 49.3 per cent ranked the two visual media over the two literary media (see Figure 3). Women who called themselves horror fans ranked visual media slightly higher, with 55.8 per cent expressing a preference for it over literary horror. For men who called themselves fans, an astoundingly high 70 per cent expressed preference for movies and television over literature, with 67.5 per cent stating that their format of preference was the horror movie.

Figure 3: Male Respondents (Top) Compared to Female Respondents

Women ranked Psycho (45 per cent), Alien

(30.2 per cent), The Ring (22.2 per cent) and Bram Stoker’s

Dracula (20.1 per cent) as their top four movies, which also happened

to correspond with their views of the films’ overall quality (script,

directing, etc.). Self-described female horror fans were eclectic in

their film tastes, with only Psycho receiving more than 31

per cent of the votes. Overall, women ranked six films above the others:

• Psycho: 45 per cent

• Alien: 30.2 per cent

• The Ring: 22.2 per cent

• Bram Stoker’s Dracula: 20.1 per cent

• Signs: 19.5 per cent

• Halloween: 18.1 per cent

Again, these choices mirrored those based on film quality.

This can be compared to the top five movies identified

by males:

• Alien: 58.9 per cent

• Psycho: 30.4 per cent

• George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead: 23.2 per cent

• A Nightmare on Elm Street: 21.4 per cent

• The Terminator: 19.6 per cent

The largest differences between self-professed horror fans and non-fans for men was extreme for a few films. Texas Chainsaw Massacre was ranked among favourites by 17.5 per cent of the men who claimed to be horror fans, while only 5 per cent found that it had any artistic merit. Neither A Nightmare on Elm Street nor The Terminator ranked well for direction, acting, script quality, etc., with both getting less than 8 per cent of the votes. One of the major differences between male and female horror fans when it comes to film can be inferred from this – that women base their choices on quality to a much larger degree than men. Male non-fans ranked The Terminator very highly (50 per cent as a favourite; 43.8 per cent for quality) and were even more generous to Alien (68.8 per cent as a favourite; 62.5 per cent for quality), showing perhaps an openness to horror when it is presented in a crossover format, such as science fiction horror. The other striking difference between fan and non-fan male respondents was the idea of what constituted a quality horror film. Non-fans ranked A Nightmare on Elm Street much lower than did fans, for example, but ranked The Terminator much higher, in both cases by ten or more percentage points.

The film choices which included active female heroines were Alien, The Descent (which has an all female cast), Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Tom Savini’s Night of the Living Dead remake, A Nightmare on Elm Street and The Ring. It is notable that Ripley of Alien, arguably the most active of horror movie heroines, resonated with men as a group more than she did with women as a group. Overall, two of the top five films noted by men contained these active heroines, while women identified three movies with active heroines in their favourites. The passive lead/cornered heroine (I draw a distinction here between the active heroine, who takes the fight to the monster, and the passive lead/cornered heroine, who fights only once she has run out of places to flee, or is trapped in an enclosed area) was represented in Halloween, The Stepfather and The Terminator. The passive lead, in other words, the woman who continues to run and/or has to be saved by someone else, was well represented in films such as Candyman, Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, Psycho, Texas Chainsaw Massacre and the original War of the Worlds. Women chose as their favourite a film with a passive lead, Psycho, by a relatively large margin. However, females who identify themselves as fans ranked highly two films with an active heroine, Alien (28.4 per cent) and The Ring (26.3 per cent), among their favourites. There was a smaller margin between those two films and the overall favourite, Psycho (40 per cent), than was reported by women overall. For all women, Alien trailed Psycho by 14.8 per cent, while it trailed by only 11.6 per cent among fans. The Ring trailed Psycho by 22.8 per cent when ranked by all women, but only by 13.7 per cent when ranked solely by female fans.

An even more telling tale can be seen in women’s

answers to the open ended question, ‘In your opinion, what is

the scariest horror film ever made?’ Three films, The Exorcist

(26 respondents), Psycho (15 respondents), and Texas

Chainsaw Massacre (10 respondents) topped the diverse list. These

three films feature a passive female who must be saved by a deus ex

machina device. So, while female respondents may not have favoured the

active heroine per se, they had a good sense of the ominous message

behind the passive lead. Only one film showed up consistently among

male respondents’ answers, that being The Exorcist, which

was named by 10 of the 56 males who answered the question.(4)

V. Where Are You Going? Where Have You Been?

The question that is at the crux of this survey was saved until near

the end, in order to deemphasise it. Males responded to ‘Do you

feel that roles for women in horror literature and film have evolved?’

with an overwhelming sense that they had. Nearly 84 per cent (83.9 per

cent, to be exact) of the 56 men who responded to this question answered

YES. The follow-up statement, ‘In one or two sentences, explain

how you feel roles for women have evolved in horror literature and film’,

led to discussions of earlier roles for women in horror portraying them

as helpless, less defined, easily victimised, intimidated, passive and

sexual, whereas they have evolved to most importantly become protagonists,

rather than simply background material. Men cited the more modern horror

heroine’s fighting skills, her aggressiveness and assertiveness,

her heightened intelligence, her confidence, and to a lesser extent,

her ability to carry on witty repartee, as important signposts of an

evolution. One particularly insightful comment summed up the overall

sense: ‘Although much disparity remains, woman (sic) in horror

literature and film have evolved from a purely victimized or villainous

role into at least the possibility of being heroic or at least multi-dimensional.’

Women were much less sure about the evolution of the female heroine, with only 67.1 per cent of the 149 women who responded answering in the affirmative. One of the better comments from female respondents read, ‘women are not just victims anymore. They are fighters, instigators, good, evil, shades of gray.’ Another female respondent stated that ‘now women are sometimes cast as heroines. In many roles, they are not portrayed as completely helpless, but have a power or strength that is inherent in their natures. Frequently a woman will figure out the problem or solve it. In addition, women have also been cast as villains or evil characters. This is a change from the roles women played in earlier stories, novels and movies: the token female, usually attractive, who is the love interest of the hero and the victim/target of the monster, or the primary person at risk.’ Overall, women latched on to many of the same traits as did men when comparing earlier horror roles for women with current ones: weakness becoming strength, passivity becoming aggressiveness, and so on. A handful of women resonated with the character Ripley as being a departure from the earlier woman-in-trouble, and quite a few noted that the degrading sex scenes seemed to be disappearing.

A similar question pertaining to male roles in horror was enlightening. When asked ‘Do you feel that roles for men have evolved in horror literature and film’, 63.3 per cent of the female respondents answered negatively. However, very few of the women who answered in the negative answered the follow-up, which asked for a brief discussion. On the other hand, of the 33.7 per cent who thought men had evolved, most left some kind of comment, many of which were insightful, such as ‘Men are more frequently victimized; in Hostel, all the men were demoted helpless victims. The men in recent horror films, like the Saw trilogy, are nothing but apes whereas years ago they were the masterminds.’ Men were even more apt to see masculine roles as stagnant, with 67.9 per cent of the 53 respondents answering that roles for men in horror had not evolved, and only 32.1 per cent answering that they had.

In Femspec and Popular Culture Review, Gina Wisker and Wheeler Winston Dixon, respectively, chronicle the evolution of the horror text as envisioned by women. Wisker (2001) cites the literary examples of Angela Carter, Pat Califa, Katherine Forrest and Cheri Scotch as female writers who reinvent the genre by creating women who cannot easily be categorised as victim or femme fatale, as they modulate between the polarities of good and evil, often transgressing taboos. Dixon (1996) points out similar pioneers of the genre in film, namely Kathryn Bigelow, Stephanie Rothman, Kristine Peterson, Katt Shea Ruben and Amy Jones, all of whom she argues stretch the boundaries of horror film by challenging the typical roles assigned to women. The results of my survey indicate that indeed both the male and female members of the horror audience are largely aware of these trends. This perhaps explains the larger than expected female audience for the genre. One of the more interesting findings of the survey is that nearly half (49.3 per cent) of the women who responded to the question asking for their preference between literary and film media stated that they preferred the horror film to the written horror text. While this was some 12 percentage points lower than that of men, it indicates that women do not consider the horror film to be distasteful. Women seem to be reacting to the evolution of horror away from the purely misogynistic, dichotomous texts that objectify female characters, stand in judgment over their ‘lewd’ behaviour, and punish what they consider to be offenders with cruelty. As horror fictions continue to evolve, towards possibly even more films with all female or predominantly female casts, or towards more novels featuring strong women who break out of the victim mould (and hopefully toward male characters who challenge what both men and women saw as hopelessly predictable roles), more women will come to the genre as fans – without seeing anything traitorous in their behaviour.

Notes

1 In Publisher’s Weekly, Sept. 20, 1993, Robert K. J.

Killheffer, in ‘Rising from the Grave’, notes that a 1988

Gallup organisation study showed that there were at least two dominant

segments in the horror audience: young males and older, educated individuals,

mostly females. Earlier, in the New York Review of Science Fiction,

November 1991, David G. Hartwell, in ‘Notes on the Evolution of

Horror Literature’, wrote that this aforementioned Gallup poll

indicated that the teenaged readership for horror is almost exclusively

male, but that much of the most popular horror is read by women. Hartwell

added that 60% of the adult audience is female, namely women in their

30s and 40s. This information also appears in Hartwell’s introduction

to the anthology Foundations of Fear (Tor, 1992). The Gallup

poll itself can be found in the Gallup Annual Report on Book Buying

(Princeton-Gallup, 1988).

2 Heterosexual women made up 85.6% per cent of the 215 females who took the survey, with 4.7% per cent identifying themselves as homosexual, and 9.8% per cent as bisexual. Of the 82 males who answered this question in the survey, 79.3% identified themselves as heterosexual, 18.3% stated they were homosexual, and 2.4% responded that they were bisexual.

3 In order to avoid getting the obvious answers of King, Rice and Koontz only, I asked respondents to identify three favourites. The list was populated with about 20 names, including well known blockbuster authors such as the aforementioned, and lesser known favourites. I purposefully included female and African-American authors, and tried to limit responses to both authors who write strong female characters and those who write mainly male characters, without labelling either as such.

4 No other film was named by more than four women or men.

Works Cited

Barker, Martin (2003), ‘Assessing the “Quality” in

Qualitative Research: The Case of Text-Audience Relations’, European

Journal of Communication 18.3, pp. 315-35.

Cherry, Brigid (1999), ‘Refusing to Refuse to Look: Female Viewers of the Horror Film’, in eds. Melvyn Stokes and Richard Maltby, Identifying Hollywood's Audiences: Cultural Identity and the Movies (London: BFI), pp. 187-203.

Clover, Carol (1992), Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film (London: BFI).

Cowan, Gloria and O’Brien, Margaret (1990), ‘Gender and Survival vs. Death in Slasher Films: A Content Analysis’, Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 23.3/4, pp. 187-196.

Dixon, Wheeler Winston (1996), ‘Gender Approaches

to Directing the Horror Film: Women Filmmakers and the Mechanisms of

the Gothic’, Popular Culture Review 7.1, pp. 121-34.

Harris, Richard Jackson, et al. (2000), ‘Young Men’s and

Women’s Different Autobiographical Memories of the Experience

of Seeing Frightening Movies on a Date’, Media Psychology

2.3, pp. 245-68.

Hartwell, David (1992), (ed.) Foundations of Fear (New York: T. Doherty-Tor).

Hicks, Deborah and Dolan, Tami K. (2003), ‘Haunted Landscapes and Girlhood Imaginations: The Power of Horror Fictions for Marginalised Readers’, Changing English 10.1, pp. 45-57.

Kendall, Kathleen (2002), ‘Who Are You Afraid Of?: Young Women as Consumers and Producers of Horror Films’, Femspec 4.1, pp. 82.

Killheffer, Robert K. J. (1993), ‘Rising from the Grave: Horror’, Publishers’ Weekly 240. 38 (Sept. 20, 1993), pp. 43-47.

Linz, Daniel and Donnerstein, Edward (1994), ‘Sex and Violence in Slasher Films: A Reinterpretation’, Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 38.2, Spring, pp. 243-46.

Markovitz, Jonathan (2000), ‘Female Paranoia as

Survival Skill: Reason or Pathology in A Nightmare on Elm Street’,

QRFV: Quarterly Review of Film and Video 17.3, pp. 211-20.

Molitor, Fred and. Sapolsky, Barry S. (1993), ‘Sex, Violence,

and Victimization in Slasher Films’, Journal of Broadcasting

and Electronic Media 37.2, Spring, pp. 233-42.

--- (1994), ‘Violence Towards Women in Slasher Films: A Reply to Linz and Donnerstein’, Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 38.2, Spring, pp. 247-50.

Nolan, Justin M., and Gary W. Ryan, ‘Fear and Loathing at the Cineplex’, Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 42.1/2 (2000): 39-57. Available online: <http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m2294/is_2000_Jan/ai_63016015>.

Pinedo, Isabel Cristina (1997), Recreational Terror: Women and the Pleasures of Horror Film Viewing (Albany: SUNY Press).

Sapolsky, Barry S., Molitor, Fred and Luque, Sarah (2003), ‘Sex and Violence in Slasher Films: Re-Examining the Assumptions’, Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 80.1, Spring, pp. 28-38.

Williams, Linda (1991), ‘Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess’, Film Quarterly 44.4, pp. 2-13.

Wilson, Michael (2000), ‘The Point of Horror: The Relationship between Teenage Popular Horror Fiction and the Oral Repertoire’, Children's Literature in Education 31.1, pp. 1-9.

Wisker, Gina (2001), ‘Women’s Horror as Erotic

Transgression’, Femspec 3.1, p. 44.