[an error occurred while processing this directive]

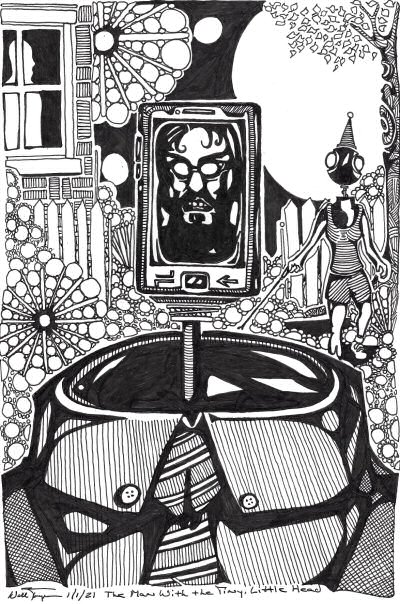

Artwork: The Man with the Tiny Little Head by Will Jacques

Magic Made Easy

William H. Wandless

When I was eight years old my mother took me to see a

magic show. The last, best trick involved a stack of four curtained

boxes on a low table.

The magician drew back the curtains on all four boxes to show they were

empty, then dropped two rabbits, a black one and a white one, into the

top box. He closed the curtains on the top two boxes, hit the uppermost

one with an oversized mallet, peeked behind the curtain, and winced.

When he threw back the top curtain for the audience, however, the two

rabbits had vanished; in the box below it, he revealed with a flourish,

one white rabbit with black spots had materialized. He shook his head,

removed the top box from the stack, closed the curtains on the three

remaining boxes, whacked the box that held the spotted rabbit, and revealed

a gray rabbit that had appeared in the second box from the bottom. Clearly

exasperated, he smacked that box and the gray rabbit vanished. From

the last box he withdrew a stuffed white rabbit in a pair of black overalls,

which he gave to me.

The magician invited me and my mother backstage to show us how the trick was done, but I didn’t want to go. If you like how things turn out it’s best not to question how they got that way.

I came by that knowledge honestly. When I was nine or ten my mother and father divorced. They sat me down and explained what was happening; they wanted me to know they had fallen out of love but they both still loved me. It would hurt, they told me, but we would be better off as a family in the end. I don’t remember the particulars all that well. Boxes stacked up in the garage, at any rate, and one day my mother was gone. My father said it was okay for me to cry, but I don’t remember crying. I saw my mother twice a week after that, and when we were together she always made a fuss about my being there, like it was a special occasion. Eventually my father found a new girlfriend, and my mother tried even harder to make my visits indulgent. We went to carnivals and shows, she made me my favorite meals, and she gave me little presents. At home my father’s girlfriend worked to earn my affection by being both attentive and permissive. I could get away with almost anything. When they got married I had two birthdays, two Christmases, and twice as many trips to the lakes and the mountains to visit with grandparents over summer vacation. My father divorced her, too, and a year later my third mother moved in. We don’t keep in touch very much anymore, but she might have been the best of the three.

My mothers said my father couldn’t keep a wife because work took too much out of him. I liked visiting my father at work, though, and when he was between wives I would go to see him right after school. He owned a high-end watch shop, and once or twice a day he’d sit on a stool at a drafting table by the front window and pretend to repair an antique watch. When he worked the window he’d wear a visor, a jeweler’s magnifying glass, and a brown apron with a row of shallow pockets for tiny pry bars, screwdrivers, tweezers, brushes, and needle-nosed pliers. I always thought he looked like Geppetto from Pinocchio. Sometimes he’d hold the barrel of a watch up to the light, take out a rotary tool, and act like he was buffing out some minuscule imperfection only he could see. All the repairs were actually done by Mr. Chatterjee in the back room.

People are willing to pay a premium for a good illusion. We like to believe what we have is special and warrants special treatment, and we have a fixed image in our minds of what that treatment ought to look like. What we really get is less important than what we imagine we’ve gotten. All the cogs and crystals in watches nowadays are interchangeable, but that’s not a thought we like to think.

It probably would have been easy to step into my father’s shoes, but I didn’t relish the prospect of sitting in that box, looking out that window. When you’re young the idea of being your own man seems awfully appealing, however unrealistic that dream might be. I thought I might open up my own place and repair electronics instead. Besides, I’ve always preferred digital watches. On the inside nothing moves, but the faces keep on changing.

It took me weeks to decide how I would tell my father I didn’t want to take over the shop. I was sure he would be disappointed, and he was. We had a long talk, but I was firm and respectful, and he agreed I was equipped to make my own way in the world. Two weeks after our conversation my father replaced me as his successor-to-be with one of my stepbrothers, but he didn’t live long enough to train him up or see the transition through. The family decided to sell my father’s shop in the end rather than try to keep it up as some kind of living legacy. I drive past the place where it was every time I go downtown. It’s a pawn shop now.

I inherited plenty of money to set myself up, so I did what they taught me to do in Business 101. I leased a boutique in a high-traffic location near the white-collar district. I shaved every day. I wore clean button-down shirts, Oxford shoes, ties, and good cologne. I smiled and shook hands, handed out my glossy new business cards. I hemorrhaged money for six months and finally folded.

It didn’t take long for me to figure out my mistake; I visited a dozen computer repair shops in adjacent cities, saw what I needed to see, and revised my business plan. The show was essentially the same, but the staging was all wrong. Now I have a place in a strip mall between a dollar store and a pizzeria. I wear throwback tee shirts featuring games I’ve never played or movies I’ve never seen and sit behind a display case with a microwave burrito and an open bag of tortilla chips. Customers have a strong idea of the disheveled tech guru they want working on their phones and tablets, so that’s what I let them see. I think we get hung up clinging to visions of what we should do and what we should be, when going with the flow and adapting to our circumstances is an easier and far more practical way of getting what we want. All we need to do is commit to the role.

The week after I opened I came across an orange tabby poking around the delivery run in the alley around back. He wore a pink collar with a jingling bell on it; his license said his name was Bailey, and his owner lived in the apartment complex a few blocks over. He came back day after day to sniff at the trash cans behind the pizzeria and the Chinese takeout place, so I reeled him in with shrimp fried rice and little bits of rotisserie chicken. When we were on petting terms I took him inside, threw away his collar, and named him Jonesy. He’s mine now and lives in the store. I reckon he’s just as well off as he was before. I doubt he can tell the difference.

I started dating a woman named Lydia not long after that. She worked the reception desk at the car dealership across the way and brought in a Fitbit for me to fix. I think she liked the idea of the kind of guy who would own a shop like mine and adopt a cat like Jonesy, a guy with limited ambition and conventional expectations. As far as I could tell things were going well, but it all ended after a few months. She said she felt like she couldn’t be herself when she was around me. I’m not sure I’ll ever know what she meant; I always felt like myself when I was around her.

It’s strange to think she could understand herself in reference to me, but I guess I’ve seen stranger. Every day people bring their gadgets in and declare their allegiance to some brand or company, and every day I replace their touchscreens, chipsets, sensors, and memory with parts from the same wholesaler. The distinctions are all in their heads. It’s like when I go to fetch groceries on Thursday nights. If I don’t much feel like shopping I’ll just wander around the store until someone leaves their cart behind to grab something they forgot from another aisle. I’ll take the cart up to the register, settle up with the cashier, and take my groceries home. People like to define themselves by their food – they’re paleo, they’re vegan, they’re kosher – but the body doesn’t care so long as it gets fed. It’s stupid to make up reasons to be picky.

It’s like the trick with the rabbits. We see the trick, go backstage to learn how it’s done, and strut around acting like we’re savvier than when we started. We know it’s not magic, just misdirection and substitution, and armed with that insight we imagine we’re too shrewd to be taken in by any of life’s little tricks. But as soon as we leave the theater we go back to believing in magic. We think we’re doing something new, something special; we think we know how things stand, how to get what we want, how to become what we were meant to be. We make choices and insist we’ve made the right ones, ignoring the fact that just about any other choice we might have made would have worked out just as well. We make our corrections and forget we ever made mistakes in the first place. Every time we glimpse anything that might ruin our illusions we just look away.

At the shop last week an older customer came in to see if he could get a GPS navigator fixed. He said he couldn’t live without it. I showed him how his phone could do all the mapping the navigator does, and by the time he left a woman with a British accent was giving him turn-by-turn directions. Just like magic. He sold me the navigator for ten bucks; I figured I could break it down for parts. But a thought occurred to me, so I fixed the GPS and turned it on.

The unit was an older one, and it had about sixty addresses stored. Most were in town, but at the bottom of the list were a dozen locations more than a hundred miles away. I picked one and headed out early this morning.

The navigator led me to a gray house with white trim and a black front door. I drove past it a few times. A thin man left in a blue sedan a little before eight o’clock; I saw a maroon SUV in the garage. A woman who lived in the house walked two boys to a bus stop at the end of the street a little while later and tidied up in the kitchen when she returned. I watched her doing yoga in front of the TV in the living room for a while and then drove home. Before I left I waved to a neighbor who was out walking his dog, and he waved back. It seems like a nice place, as nice as any I’m likely to find.

I’ll go back after lunch with my things so I can meet the boys after school and be ready when the father comes home. I’m a little taller and slimmer than he is, but I doubt they’ll notice the difference. The wife has a nice smile.

I think I’ll name her Lydia.

Home