[an error occurred while processing this directive]

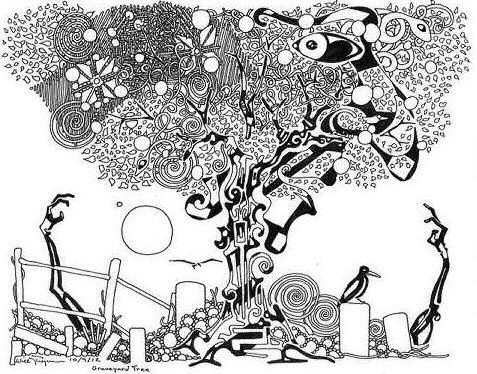

Artwork: Graveyard Tree by Will Jacques

Rookery Cottage

Liam Wisker

So I shot the big bastard in the head, which was just what he deserved. Then there were the parts, all his little pieces, and all of them would eventually become stinking rotten piles.

Do you dig a grave in your own back garden during the midnight hours without getting noticed? Hidden in the dirt under our oak tree? The noise would wake the ravens, the branches would become alive and all hell would break loose. So I didn’t have any choice. Just like in his living state he was still capable of squandering all of my options. Thwarting any way out I ever had. As if I ever had any. He never made anything easy.

A junior hacksaw grinds through bone with as much efficiency as using a rusty nail to remove bacon from between one’s back molars. Not just useless, but perilous and with the capacity to really carve me up, long term. It took ages and he remained slack jawed throughout. His tongue lolling out his mouth as it always did while he snored next to me. Once he was in pieces so small I could clasp them in one hand I ran all the limbs and fiddly pieces of bone and tendon through the wood-chipper. Watching him disappear was a bit strange. It felt like love, or maybe just pity, something unfamiliar was running through my brain. Not love; the love went the first time he lashed out. Not pity either, that went during the final straw when he cracked my nose open with the butt of his shotgun. I gave him everything he wanted and it still was never enough. I even allowed the abominations he requested in bed. He brought it on himself. He brought it on himself.

I set out on something we did every year. Selling the remaining soil bags we always have left over from the farm, to locals, to anyone with a patch really. I can’t remember how this started. It must have been his idea. I think he wanted to do this so he could always feel like he had some ownership of everyone’s garden, every allotment, or that he was at least part of it all. Now he certainly will be part of it all, he’s getting his wish. After I had finished the job with the wood-chipper I distributed his remains amongst the bags. So I guess he got what he wanted, he will always be part of the landscape.

The first road on our usual route is a really good seller. The houses are outrageously big, as are the gardens at the back. I drove to the end expecting to see the old lady who lives there. She always takes a bag or two to grow her hanging baskets. She wasn’t there, so sad, I knew there was a chance she had passed away. The boy who came to the gate had her features and the house hadn’t changed; I figured he was her son, or maybe grandson.

“Hi, hi. Me and my husband have been doing this for years. It’s soil, top quality and cheap as chips. Is the little old lady not here?” I asked.

“You mean Gran? She died, I’m afraid, in December. I’ve got the place ’till we find a buyer. I’ll take a couple, though, ’cos, well, the boys and I have a little, shall we say, hydroponics expedition,” said the young man.

“Oh, well, anything’s good if it makes you happy,” I said, knowing full well what he was growing.

“Nobody’s committing any crime here. It’s just a bit of Jamaican tobacco,” he replied, laughing, so I chuckled back.

“Cheers, see you soon,” I said, getting back into our Jeep. The rear space can only carry ten bags, so I had a few days left to shift the lot. My process had been so random that at any given time any one of my customers could be getting a bit of brain or an ear lobe. Who knew? I squelched it down so much you would think a chip of spine was just bird crap or rabbit droppings.

A lot of the characters that buy on that road weren’t home that first day so it wasn’t such a good seller. I sold two more to the couple who live in the house on the corner; they always take two.

I did something I only ever got to do when he was away on business. I sat in the garden with a few glasses of wine and read. The only times I moved were when the oak tree started blocking out the sun as it crossed the sky above me. It’s a giant beauty of a tree. A few years ago he wanted to fell it to put up another pointless outhouse. I said no. Pointed to the birds’ nests, and the shade it provided over the lawn, and he gave in. Possibly the only time I ever won anything. Every evening the big raven flew from her nest. It must be female because it doesn’t screech selfishly at me whenever I go near the tree. I watched her fly away into the sunset.

It got dark, too dark to read, so I went in through the French doors to watch some telly. With nobody there to bark orders in my face I could do whatever I wanted. Then off to bed, alone, what a feeling it was. As I drifted away I remember wondering if I would ever bother to replace him with another man. A gentle man who left me the time and space I need to live happily in my own skin. And whether I even wanted another one after the horrors of the last. He had driven me to murder, then body mutilation, then my own take on a forensic cover-up. They can’t all be that bad. My last thoughts were if I should just sell the place and start again somewhere else. That’s when I drifted away.

Outside, in the darkness, that raven had flown from her roost and gone hunting into the night, many miles from her oak tree roost at Rookery Cottage. Busy, on a haunt above the trees, unseen in her blackness, she can glide forever. A metallic black that shimmers until it vanishes into the night, chasing the smells of death in the air, waiting for the perfect scent to prick up her interest, thereby choosing the location for dinner. Whenever the scent comes, the bird knows.

Delicately she lands like a thousand times before. Incognito, so she doesn’t disturb another scavenger and be discovered, under those delicate wings lies the beating heart of a night dweller, and she keeps them flawless and perfect. They ruffle into place, her form now flaunted out for all to see. The scent that brought her there was strong. It reminded her of a scent she knows intrinsically from her youth, from her childhood nest high up above a ‘beep beep’, as her parents called it. She knew its true name though: ‘hospital’. That same smell festered in the dirt around her feet. Swirling around her, lingering enticingly in the breeze, she knew it would only be a matter of time before another night dweller latched on.

Eagerly she sifted through the soil and mulch, trying to locate that special morsel that had brought her down. Hospital means humans and humans mean food: bread crusts, meat scraps, anything. Many humans had passed under her childhood roost in flashing lights and never left; that smell, however, had always remained. She knew a reward was waiting. Frustrated by the unanswered promise she searched further for the goods, continuing to peck into the soil to uncover the truth behind the scent.

Then, the answer came to her in the form of a severed digit of a human finger, still with a wedding ring embedded in the skin. She split the finger open with one stab of her beak. She was rewarded with flesh and tendons, bone and nail. A well deserved meal for a thoroughly deserving bird.

Meal devoured she took back to the skies, once again returning to her roost high atop the huge oak tree. But what goes in must come out, and this raven is no fool. She knows not to rest on a full stomach, nor to take to her nest still covered in the dirt and soil her feathers accumulated during her flight. She let rip, ejecting much of her breakfast along with a healthy dose of her dinner down to the soil under her roost. A shake of the feathers and a grate of her claws and, just like that, she’s cleansed of her day and ready for bed. Into her nest she shuffled, in her branch high in the oak tree.

At its foot her droppings had settled, dissolving away into the soil as if nothing had ever dropped, disappearing like seeds after a gardener’s raked them in. Gradually, dark became light as the morning sun lit up the world, bringing it back to life.

I woke up feeling good, ready to do business. I headed out to the industrial fields, the giant, sprawling ones owned by the supermarkets, where crops are grown in rows and regiments across the horizon like the landscape of another planet. There’s never a buyer on those fields, but just before they begin there’s another small patch of allotments. A couple of middle aged men were trotting over one allotment. They looked like they were there more to escape home and spend a day with a mate than to turn the patch over. They took two bags. The bigger guy tore one open on the spot. I froze in sheer panic that I would get found out then and there. Somehow, I thought, that joyless lolling tongue would flop out onto the soil at our feet and point its blameful blood vessels at me. Nothing came, though. It didn’t even smell, and there wasn’t any congealing, which was a pleasant surprise. The dry soil must have dried out Bill’s juices. Then he started flicking spade loads over the veggie patch. Fair enough, I thought. That’s exactly how I work.

“I like your style; it’s like what I do. It’ll make a great top layer for whatever you grow. Very fertile,” I said.

“Why are you selling it?” asked the littler of the two.

“Me and my husband always have lots left over at the farm, so we sell the leftovers in springtime. He’s very ill, so I’m doing it.”

“Well, thanks. Send hubby our best.”

“Will do,” I shouted, hopping back into the Jeep, watching as the littler of the two started turning the soil over, mixing it all in. Best to have a mixture of new soil and the old; it just adds some nice new nutrients to an already proven patch. I sold a couple more then packed it in for the day to go home and enjoy the garden.

I awoke to sun shining in through the bedroom window and the birds singing in the trees. It felt fresh, like it was a new start, but it wasn’t new. I felt just as refreshed the morning before, and looked forward to the same feeling for every morning to come. All that was left was to shift the remaining five bags, and finally life could begin again, as if Bill had never entered it. Looking out the windows at my garden I could see I had left the empty bottle outside. I chose to collect it, a decision I made for myself, yet another revelation.

A crispy dew had formed on the lawn that morning. It was so crunchy it just added to my feeling of content. My mood was so cheerful I felt like I was performing every step to an increasingly jubilant audience. I nearly skipped the last steps to the table.

Quickly it all changed. Some smell gripped the capillaries round my tonsils and the back of my throat. I knew the smell; it was death. It was a small creature, less imposing, slightly more bearable than a five-day-old, bloated horse corpse. It was still putrid. It made me retch but nothing came up. My moment had been ruined; my imagined audience had booed me offstage and left.

I thought a fox must have dumped its kill close by. In the farming business, death is part of life, you get used to it. Not often in that form though. You only get exposed when the death is fresh, as the meat is carted off to market. But that smell by the oak tree, that stagnant decomposition, and the inquisitive, penetrating white maggots my subconscious layered on top for me, I’ll never get used to that smell.

There was nothing there except a stalk that had poked its way out from the topsoil. I had never seen it before; it looked almost like a clover but with a bulkier base. The birds bring stuff in from God knows where, it’s not the first time I had seen something unusual pop up in the garden.

I drove up over the hill then down towards the lowland valley into allotment land. That’s where the real business tends to show itself. The whole thing stretches out as you drive down the hill, it’s all just brown in early March, or mulchy green where the allotment owners got lazy and left last year’s remains to rot. A lot of them are rich and send their teenage kids or whoever else they can rustle up to do the work for them, a pattern I always spot at the click of a finger, because everything happens in one day, then it gets left, then another day a few days later another huge shift is put in. Young kids simply aren’t the sorts to potter every day. They want to get in, put in a hefty shift of a whole day’s lifting and planting, then go off and spend their earnings down the pub. Driving down that hill you see which is which, and it doesn’t matter, they all buy. The pottering oldies might buy one for today; the smoking youths might take two or three. At least he wasn’t with me, telling all the gardeners he’d done all the work. It was getting done without him.

The owner was away but the ravens were awake at Rookery Cottage. Daylight was dissolving; the night shift would be upon them very soon. The inhabitant of the proudest nest, up high in the oak tree, was readying herself, only a few hours to tick by before another night flight. In her rustlings she could see something new now protruded from the dirt beneath her roost. Something unnatural, underdeveloped by design, suggesting the full form was yet to show.

Unlike any other plant, it looked like it longed to be there, displaying a lust for life like no other, like it would devour its own children to maintain some earthly presence – a ravenous triffid, silently gorging upon every nutrient in its vicinity. Grass nearby had begun to brown and die. The daffodils had wilted, flattened into the mud. An unseen network of roots were forming, supping on whatever they could, depleting it all while continually pulsing lifeblood through the veins of the pod above.

The pod itself pulsed light green, shaped like a diamond on a playing card, not like one you might see in a wedding ring. Every so often a rumbling and swelling was erupting from inside, like something internal wished to rip itself from its tomb. Whatever it was inside, it lacked the tools to escape. A blade, some spike to pierce the slimy exterior, even a fingernail would do the trick. There it was under the oak tree, wriggling like a maggot, waiting for something to pop the outer layer.

Finally, I arrived home on the last day, when the last bags had gone. I can remember it clearly – the house was empty for me. I was at peace in my own home at last. I hadn’t changed the bed sheets because of him. I felt his presence in our bedroom right up to the point when that last bag was finally sold. The need to cleanse him off sent me up to our bedroom. All the bedding found its way to the bottom of the stairs. In a trance, I just tore the whole lot off the bed and stripped the room bare. I replaced it all with bedding from my life before we met, stuff I liked but was kept from sleeping in. It all felt fresh, and the beginning of a new chapter, where the air around me was my own to breathe. The house was mine. I would have the lounge to myself for the evening.

There was a squeaking I heard while I sat with my TV. A gale had picked up outside, so I assumed it was nothing but the wind catching loose guttering or a tree being harassed by the swirling rush. It persisted through the hours I watched that night.

A tap came rattling against the sliding window, just like a tiny stone had hit it. It was only once, so I let it lie. What I really thought was everything had been going so well recently that I would have to face something to bring me back down to earth. A new infestation of rats perhaps, that would do the trick. Sure enough came another scratching, a flitting scuttle at the foot of the window, much like the sound a large rat makes when it’s fetching for a way in.

Again came the noise. It wasn’t random. Wind shakes trees by chance, luck, this had become different, rhythmic, like a tip-TAP-tip-TAP, then another tip-TAP-tip-TAP.

Opening the curtains I looked out across the garden. I had to squint as night closed in. My eyes became accustomed to the dark, and my vision became clear. I saw my table and my chair, waiting for my return. Then behind them was the oak tree. Before the mighty tree was a shape like nothing I had ever seen in any pursuit, neither in agriculture nor in horticulture, unrecognisable even to someone like me. If anything it resembled a freestanding fresh knife wound that had just burst its stitches.

That was it for me; I no longer believed in a happy ending. I could never escape. What could it be, this new horror? Simply life deciding to erect a sign in my path, saying – ‘Happiness is full: do not try to get in.’ As I stared at the shape I noticed it had become hollowed out, as if it were a nutshell that had been opened, so the insides could be devoured. I drew my eyes away, unwilling to explore. My eyes retreated but were drawn to a track. I looked two, maybe three times, and every time it became clearer, leading from the thing, towards the house across the lawn and to the porch, then out of sight, as if it had entered through the back door. As if what had entered through the back door?

Bill kept a shotgun glued to the back of the sofa. I grabbed it. He never messed about with security; it would be ready to fire. Then that sound that I thought impossible came anyway. The door unlocked at the handle, then the hinges creaked it ajar.

All I could do was huddle behind the sofa, shaking uncontrollably. The shotgun rattled so much in between my trembling hands. I knew I would have to look. If it was a burglar I would prefer to just shoot him dead than let it get messy. Footsteps came inside. Not the clean cut echo sound of a boot landing on wood, but a slosh, like you make when your boots are drenched through. I popped my face over the top of the sofa to catch a glimpse, nothing there, just the kitchen. Except that from where I was, cowering behind the sofa, my view was blocked by the shape of the house. I couldn’t see what had entered.

Then I heard it breathe, and it sounded just like Bill – Bill when he was nice, when he was sober, or having a good day – light, not the heaving, angry rasp of adrenaline that made me kill him in the first place. It couldn’t be. I knew it couldn’t be. So I stood to face it as it emerged into my kitchen.

Bill, right there, fully clothed, dripping glutinous and wet like something raised from an oil slick. He looked less threatening, like he would be toothless in attack, like the weakest, laziest bluebottle fly that drops onto your plate like a stone, just buzzing, pathetic, the vilest kind. I would rather it be a rampant wasp zipping over my meal, so when you flick it off you feel like you have won, not like you are a killer of innocence, murdering a newborn baby just for being born.

“You. You’re dead … because I killed you. I’m sorry Bill.” He didn’t respond. I felt so many voices in my head screaming at me to get their messages across. “It’s not real, it can’t be real, so just blast him again,” said one. “Of course it’s real, he’s come back to get revenge, just shoot him again,” said another. “Whatever that is, it’s not good, so kill it,” said the last voice. Nothing has changed, nothing can get any better, it can only get worse. I knew.

So I shot him. Then I shot him. Then I shot him again. That gruesome creature crashed back into the fridge, then just lay there bleeding on itself. It bled not red but deep green. He, it, Bill, once again staring at me like a doe-eyed rag doll, that disgusting tongue lolling from his mouth. I went in on it, determined to finish the job. Just before I pulled the trigger, he opened his eyes at me. Slime drizzled down the eyelids, then dripped down his cheeks. Every visible crevice oozed green slime. The eyes staring back were nothing but a void, an empty white space where his pupils were in life, the eye without a pupil, and lids without lashes, a pitiful version of the brute.

Real or not, I blew his head clean off at point blank range, ran round the house snatching my belongings and loaded them into the Jeep. Then I went over every inch of the place, dousing everything in petrol, including him, lit it on fire and let the whole place burn. Nothing else seemed to work, so I put my trust in fire.

I stood there, bags packed, and just watched the cottage

burn itself down to the ground, right to the last shred of timber nothingness.

Then I drove away from the village, forever I hoped.

I didn’t report him missing to the police for obvious reasons.

Our closest neighbours were a five-minute walk from the farm and they

were never anything but passers by to us so they would see the remains

of our farm and cottage but have no place to ask their questions.

Bill had a childhood friend who still lived in the village, Adam, who contacted me somehow. Adam was nice enough in the times I had met him years earlier, but the phone call was an assault on me. He asked why had I left Bill? I said nothing back, and then he said,

“Wait two seconds, Bill’s here and he wants to talk to you.”

I hung up.

**************************************************************************