[an error occurred while processing this directive]

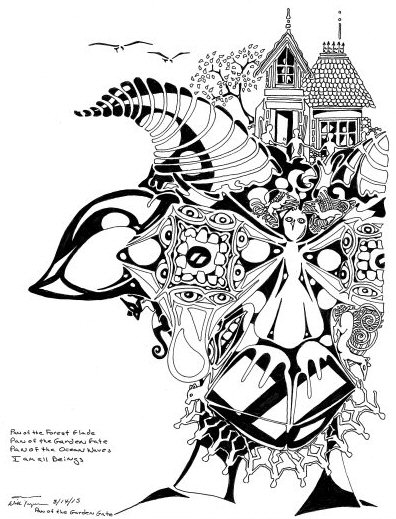

Artwork: Pan of the Garden Gate by Will

Jacques

Finding My Sister’s Tongue

Douglas Ford

My twin, when I had a twin, never said a word, so my mother called upon me to speak for both of us. I still spoke for myself but learned to say "we" a lot.

No, we didn't have a secret language, as twins often do, or supposedly do.

Before what happened with the speech therapist, my sister simply defied everyone who called upon her to speak. Even my mother. Even me. Even the doctor.

The doctor scrutinized her with a tongue suppressant while my mother and I watched. He looked deep inside her mouth, wearing a worried expression.

"She has a tongue," I said. The doctor looked away from the open mouth, and I met his gaze.

I knew about the tongue because I held her down once and pried open her mouth to see. With my fingers I squeezed the pink gob of flesh in her mouth and felt its realness.

Before what happened with the speech therapist, I could trust in the realness of what I saw. What I felt.

I didn't intend to hurt her, but she screamed, so I knew she could scream. I didn't tell the doctor that. One stern look was enough.

The doctor turned it on my mother instead. "Speech therapy," he said. “She needs it.”

Because of the way our mother protested, I thought he meant she needed a shot. With a needle. At the time, most of our mother's concerns seemed mysterious to me, but I understood enough to know that she wouldn't let anyone give us any sort of shot that would interfere with our growing. No vaccinations, no pills. We had strong bodies, she said. Our bodies could fight off measles and chicken pox on their own, without any help from the poisons in needles.

Those poisons could do anything to us, she said. Chickenpox goes away after a while, but those poisons could make us slow and stupid and even dead, and those things lasted forever.

The doctor always seemed exasperated with our mother.

"There's no permanent file that this goes into," he said. "It won't affect schooling, it won't affect college. It's intervention, that's all."

"People will know. They'll label her. I don't want this marking her for life," my mother said.

"It won't. The therapist will even come to your house. This is just intervention."

"You say that word like it means something harmless."

I had not met very many men at that point in my life. I watched the doctor's face twist and pull. Later, at home, I stood in front of the mirror and tried to make my face do the same things I saw his do. I said that word slowly to my reflection. Intervention. I made little furrows appear between my eyebrows. Intervention. Standing on a stool by the sink, I turned on the water so no one could hear me, but my mother appeared in the doorway anyway, arms crossed, looking furious.

But instead of yelling, she spoke in a slow, clear voice. Her eyes kept yelling, but her voice sounded far away. "You need to do it for her," she said. "Meet with the therapist in her place. Show him you can talk."

I used one of the doctor's facial expressions. "I don't want to."

"You could always talk. Practically came out of me talking. You have to do this. Do it for your sister."

"She can talk. She just doesn't want to."

My mother surprised me by saying, "I know. But until she lets go of that stubbornness, you'll do this for her. Be her. Just for a little while."

I didn't know what a speech therapist would say or do. I imagined someone like the doctor, another man dressed in a white coat with a stethoscope. Would he look under my dress the way the doctor did sometimes? Would he write down all the things I said and make me speak carefully? Sometimes I said things without meaning to, but when I found my sister in the living room, looking into the jar that held the caterpillar from our mother's garden, I meant every mean word that came out of my mouth.

She liked to tend the garden with our mother. Every morning they watered plants together while I stayed inside and watched them through the window. Just the other day my sister found the caterpillar and our mother showed her how you could put it inside a mason jar with a spruce of milkweed where it would eat and get fat and eventually form a chrysalis so it could turn into a butterfly.

My sister liked to sit at the table holding the mason jar and watch it by the light that flowed through the window. At night our mother always told us to pray for little things, even the caterpillar with its little yellow feelers, and as I watched my sister squeeze her eyes shut, looking so lazy and dreamlike, I thought she must be doing just that right now—praying for it.

"Because of you," I said, whispering into her ear, "I have to be with the speech therapist and have him write down all the things I say and he will maybe look under my dress."

She opened her eyes and watched the caterpillar crawling on the sprig of milkweed. Her hand reached out and unscrewed the cap, and without a glance toward me she reached in with her finger and touched it, even though our mother warned her it could sting. She smiled when she did this.

"I hate you," I said. "Hate, hate, hate you."

But she went on pretending she couldn't hear. All that ever mattered to her existed inside the jar.

"I'll smash it," I said. "When it makes itself a cocoon, I'll reach inside and squeeze it into nothing."

Her smile never went away. I wanted it to, but it stayed fixed on her face all the same.

************************************************************************

When I woke up the next morning, I found the bed next to me, her bed, empty. Normally, she never got out of bed until I did, even if she was awake first. Some mornings I would wake up because I could feel an odd tingling, and when I opened my eyes, I would see her staring at me. Her stare, I realized on those occasions, stopped my sleep. But this morning I left my bed alone and found the living room empty, too, and the kitchen as well.

Panic welled inside, filling my lungs like a balloon.

I cried for them. They left me alone.

I turned to the door leading to our mother's room. She told us to always knock if we found it closed, but I knew the room behind it was empty. I knew they had left me. I didn't know what I thought I would find as I reached for the door, but I extended my hand, still crying, and started to turn the knob.

Only the handle turned on its own. The door opened from within.

Relief came over me. I thought I would see their smiling faces coming out of hiding. Playing a little trick. All a game of hide and seek, only we decided to start while you were still sleeping.

But I didn’t know the looming figure coming out of our mother's room. I didn't recognize his pale face and the sparse, gray hair on his head and the black shoes on his feet and his even blacker eyebrows. I felt the air go out of my chest as he walked past me into the living room, his eyes never leaving me. He gestured for me to follow him as he walked toward the window ledge holding my sister's mason jar. He stopped, his back facing me.

My legs had frozen.

"Come here. Show me your pet," he said, not turning around.

I opened my mouth to speak, but I panted instead. I wanted to ask him what he'd done with my mother and sister, but fear ebbed through me and robbed me of speech.

He turned his head his slightly and regarded me with one black eye.

"Come," he repeated. "I want to talk to you."

That word, talk, broke through to me. It called up the memory of the doctor and what he told our mother—that the speech therapist would come to our house. Only he didn't have the stethoscope around his neck, as I imagined, or any papers to gaze at over bifocals and instruments for peering into my mouth.

The man picked up the mason jar, unscrewing the lid as he turned to me. "I like this specimen," he said. "You found a poisonous one, you know." He held the caterpillar in his hand and beckoned me closer to see. Stopping just out of arm's reach, I looked at what he held in his hand. I imagined that we might count the number of legs on his body together, or describe his colors and contours. We would talk together. He would hold my cheeks and force me to wiggle my tongue into words and sounds.

But I remembered what our mother had told me. I would pretend to be my twin. I would maintain myself as someone who had never spoken. Perhaps I would remain silent and suddenly find my tongue at the end of the session, making it seem like he'd gotten the job done. Our mother didn't tell me what to expect, what to do. Would she be in trouble if he discovered the game, that I wasn't my sister?

Still, I almost spoke aloud when I saw what he held in his hand. Instead of the greens and yellows and blacks of the caterpillar my sister found, this one had a purple body and orange, prickly feelers. That's not the one, I wanted to say.

He seemed to hear me think the words because he shook his head. "It's a buck mouth caterpillar. Poisonous, but not deadly poisonous. Your sister would get very sick if it stung her. Very sick, but no, she wouldn't die." He put the caterpillar into his coat pocket. Then he reached into a different pocket and pulled forth a glass vial. He held it up for me to see.

"This," he said, "comes from my backyard, and it's very, very poisonous. Deadly poisonous."

Inside the vial, a kind of bug roughly the size of my finger peered back at me—a tendriled, spiky thing that looked like a water dweller of some sort. It had bulbous, intelligent eyes that would look more at home on a rat, and under its body trailed a purple, veiny sac that looked full and ready to burst. From that sac extended a protruding spike that dripped a white, viscous fluid.

"It can't live without secreting its poison into something," the man said. He handed me the vial. "And this one? He's fit to burst. Do you know who he should put it into?"

He leaned forward as if to search my face for an answer.

"I thought you would talk to me," he said. "I know. Say my name. Go on, that'll fix that tongue of yours."

I held my lips tight as he regarded me.

"Go on, I know you can."

I wanted to scream at him, tell him to leave our house. Go far away and never come back, never come again and never hurt me or my mother. Or my sister.

"Say it," he whispered. "Say my name. All will be fixed."

I opened my mouth to say the words, and what happened next happened so quickly that I couldn't stop it. Somehow, without me seeing him do it, he had reached into his pocket and pulled out the buck moth caterpillar, and he got into my mouth with what seemed like no effort at all, just as I opened my mouth to speak. Then he forced my jaws together as he screeched the word chew over and over again. "Chew, chew, chew." And I felt the pulpy body squirt to pieces under my teeth and tasted its sharp feelers on the roof of my mouth and my tongue, and I thought I heard it mewling like a kitten and wondered how it could make such a sound before I realized that the mewling came from me as I cried and cried as the man forced my jaws up and down, saying, "Chew, chew, chew," over and over like that, until everything went dark.

************************************************************************

Awakening, I found myself back in my room, my sister already sitting up in her own bed, watching me. My head swooned as I sat up. She kept watching, even smiling for an instant, as my stomach heaved. I could feel the poisons churning inside me, and for one terrible moment, I thought I was going to die. Instead, I vomited—greens, yellows, blacks, all coming up, all over my bed, all over my bedclothes, and through my tears I saw my sister's grinning face change. It held no sympathy for me, no love, just anger--a knowing kind of anger. And jealousy.

I clutched my stomach, understanding that she suspected what had happened, that she would have spoken the name of the man who came out of our mother's room, that I had robbed her of her special moment of speech.

Or maybe just that I had eaten her precious caterpillar.

She more than suspected, she knew, I realized, as my stomach continued to heave, and my sister ran from the room with me following, still choking on my own fluids, wanting to cry her name and beg her to stop as she ran past our mother in the living room. "What is it?" our mother said, looking first at my sister, then at me, her eyes widening at the awful mess covering me, repeating, "What is it?" as I struggled to get the words out, our mother clutching my arms and shaking me while my sister already had the mason jar in her hand and was opening it ("What is it?"), so she never saw what was inside with the milkweed, not the caterpillar, but the thing from his backyard, the thing with the dripping needle, and my sister didn't see it either until she had the jar open.

By then it had jumped on her face, the needle piercing her cheek. The sac under the needle pulsed once, twice, and seemed to deflate as everything left it and went into her. Her mouth opened and her eyes squeezed shut, but the sound of screaming came from me.

"What is it?" our mother kept asking me, so she didn't turn in time to see my sister's body slump to the floor and the thing scurry away, dragging behind it that spent, dirty needle.

************************************************************************

In the nights that I followed, when my mother closed the bedroom door on just me, she no longer told me to pray for little things. She knew no prayers ever came from me, and I realized now, that she only spoke to my sister when she left us with those words. Pray for the little things. And I know now that she said those prayers, sent them up silently, and not just for the little things.

Alone now, so did I. I heard the scratching in the walls

that my mother couldn't hear, and I prayed, prayed all night.

**************************************************************************