[an error occurred while processing this directive]

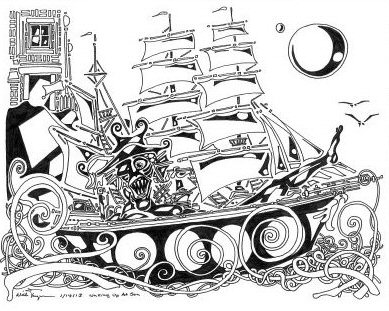

Artwork: Waking Up at Sea by Will Jacques

Smoker

Rob Bliss

When you’ve made yourself a pariah in your enlightened land, there are still undiscovered countries in which to escape. I had burned every bridge, lost all friends and family to either abandonment or death – became far too well-known to the police. They had me on their nation-wide computers down to my DNA, so I would never be free even when I was free. No government ever erases the information it obtains through fair means or foul on its citizens. My pariah status was half made by me, half by them. They maintained it when I wanted to let it go.

I waited them out. Kept my nose clean long enough to be given a pardon. But I wasn’t naïve any more – I knew ‘pardon’ was a misnomer. When I could travel again, I did. Visited several countries – mostly isolated islands – to see which one would give me the greatest anonymity.

Having lost everything, I never acquired much during my wait. No house, no car, no land, no wife, no kids. I avoided all of these to ensure that I would be able to travel light. On my last venture into the world, I found my island. Packed a single bag and didn’t have to tell any authority where I was going, how long I would be, when I was coming back.

I don’t return to places I leave.

I vanished from their radar. An old criminal who was so low on their totem pole that my wait had been uneventful – no re-arrests, no breach of probation – which meant they wouldn’t be sending their international crime-fighters to hunt me down. Still, I made sure the country I was heading to had no extradition treaty with my own.

I may miss the snow, but I’ll survive the sun. I have forty years of winter memories to reminisce over during certain holidays. But I would keep telling myself that sand and surf are a perpetual holiday. I needed to convince myself that the tropics meant freedom, whereas the arctic meant imprisonment. Easy to do.

I settled into my new nation. Learned the politics, the culture, the myriad idioms, the geography. Though all I really needed was a map. All an escaping human being ever needs, though sometimes not even that if he is truly desperate. I left the main island and its capital, its small metropolis trying to act international, cosmopolitan, civilizing itself away from its traditions. Happens in every nation, the disease of technology. Warning signs to me. I kept quiet, didn’t meld in with the new crowd … a mob was a mob, after all. If they discovered my past, they would condemn me as quickly as my old countrymen.

I found one of their remote islands. An old dead volcano that held no interest for volcanologists. A refuge for birds, most of its surface covered in white and green guano. Perfect for me. A shit who lives in shit. I had learned to accept, and exalt in, insult and derision. It was who I now was in the twilight of my life.

Lived the Crusoe existence, building a hut of bamboo and palm leaves. Returned to the larger island for necessities. I was no pure castaway, willing or able to fashion a fishing rod or spear from the jungle. I bought these things, would repair them as best I could, return to the big island if I needed replacements. But that would be years away.

The sea fed me. Couldn’t bring myself to kill a bird. Symbol of freedom. Same reason why it is forbidden to whistle in prison. I was instructed by my cellmate: “Birds sing because they’re free. You ain’t free, boy.”

I swam and lay on the beach and burned brown. My freckles bloomed year round instead of waning with the winter. I built cities of sand castles, then stomped them back into their formless grains. I screamed my problems to the salt wind and cursed the land that gave me a happy childhood, and everything else afterwards. Everything was at fault but me. The prerogative of the lone man.

I was alone but not lonely. Still, I missed a few things. Back home, to deal with the stress of my past, I smoked heavily. The island was able to break me of the habit (as prison had), but I often wished to smoke a cigarette, a cigar, a joint while watching the tropical sunset ease itself into still waters.

I made a trip to the big island. Bought a few cartons of cigarettes and boxes of cigars. Found a man in a bar who sold me marijuana seeds. Started to get drunk, but the warning signs went up. I too often tell the truth when I’m drunk. My past comes out and stains me. I couldn’t stain my new home with my truth.

Returned to my island with my bounty. Lit my first cigarette in a year with a twisted dry palm frond from my campfire. The best way to light a smoke. Dug myself a recliner in the beach sand, blew smoke at the orange sun. I felt happy.

The seeds didn’t take in the sandy soil, but I thought that might happen. I ate the seeds and got a small buzz while puffing on a cigar. I was afraid old habits would return, so I measured out my tobacco, allowing myself one cigarette a day, then onto the cigars. Twenty-five cigarettes in a pack, eight packs in a carton. They would last me approximately two years or more if I held to my schedule.

Which I didn’t. Two cigarettes a day, then three, one after each meal. By the time I got to the cigars, I was smoking all day long. But I made the cigars last longer, lighting them, putting them out, re-lighting them later on. One cigar could last a full day. But there were only so many in a box.

In ideal tropical island fashion, a girl appeared one day. Lying face-down on the beach. A canoe with its bow crushed, paddle snapped. She was ragged, worn, her long black hair tangled and stiff with salt. Wearing a thin white cotton dress, nothing else.

Beautiful, of course. These fantastic stories always involve a great

beauty washing up on shore. Life is a series of fairy tales, and sometimes

the pariah becomes the prince. I helped her to her feet, walked her

to my fire, fed her, spoke to her in one of the more predominant dialects.

She measured me with her eyes, was not afraid of me. Took off her

dress and sprawled it across a pyramid of driftwood to dry. I looked

at her nude body, then removed my ripped shorts. We sat at the fire

naked and talked. I told her I was unable to get an erection, but

didn’t want to talk about it. (Sometimes beauty is also a truth

serum.) She relaxed more, stretched out her brown legs, dug her toes

into the sand.

I wouldn’t tell her the whole truth. Only that I was from a

cold country which she had heard of, and that I wanted to leave it.

No wife, no children, parents dead, nothing to keep me pinned to the

cold.

She told me her truth. A husband back home on the main island. He beat her, got inside her mind to force her to think as he wanted her to think, crushed out the love in her heart she once had for him. He gave her chores to do while he was at work, forbade her to stray from home, even to shop for groceries. A jealous man who had to stay at her side, and when he couldn’t, he had to make sure she stayed home. Fear was the lock and key. She hadn’t seen her mother and father, her two sisters, in years. They hated him and he them, and she was forbidden to maintain contact. She had no friends, had to push away, ignore, anyone who wanted to be her friend.

She was obedient. But everyone wants to escape obedience at some point. She waited for him to head to work as she scrubbed the floor, her first chore of every day. Waited an hour after he was gone to make sure he didn’t head back.

She walked away from home, felt terrified and excited as she headed

down the road toward the beach. Glanced over her shoulder, jumped

at the tiniest sound, cars passing, reptiles in the sand, birds shooting

through the tops of trees. Her heart raced and her breath sped up

to a marathon runner’s heave.

She came to the beach, abandoned in mid-day, everyone at work, not

yet tourist season. A battered canoe lay half-buried in the sand,

weathered and worn, but it floated and had a single paddle.

With her fear to help her, her thin arms tipped rain water and settled sand out of the canoe, dragged it into the water. Got in and rowed, eyes looking back to the beach, waiting to see him running toward her, cursing her name, listing the threats, the injuries, he would do to her once she returned to land.

She wept into the fire. I cradled her. Tucked her head into my neck, felt her small body tremble. I felt uncomfortable comforting another human being again, I had been alone for so long. I held my breath as she wept, my pieta posture stiff as marble, waiting for her to move, to decide when I had comforted enough.

She raised her red eyes to me, lifted up her chin. We kissed.

We kissed. We kissed. I had forgotten what it was like to kiss. It terrified me. My heart pounded with panic. But I held my lips to hers, fascinated by the strange sensation of having my lips pressed against the lips of another person.

She slipped her hand between my legs, but I pulled her arm away, held it until she gave up trying to touch me there.

When I pulled my lips away from hers, smoke threaded from my mouth, linking her lips to mine until it dissipated.

I didn’t understand. We hadn’t been smoking. But a look of serenity softened her face, her eyes shone with love and oblivion. We kissed again and again and every time I pulled away, smoke sat in the air between us.

I told her she didn’t have to go back to her husband if she didn’t want to. But, I added, I was a man accustomed to being alone. I preferred it. I didn’t want to send her back to a house of abuse, but I also didn’t want to share my island with her. With anyone. I told her that, of course, she was beautiful, desirable, but my life had led me to this solitude, and not even beauty could sway me. Not any more.

Could she live with one of her sisters?

She stared at me with a smile in her eyes, smirking, and asked me why would she live with one of her sisters when she had a loving husband to go home to? My eyebrows wrinkled, wondering if she was playing a prank, her biography of pain really a lie for sympathy. I repeated what she had told me, but she waved it off. Oh, sure, she said, he got mad once in a while, but so did everyone. It was nothing she couldn’t handle.

I was confused. Reminded her again of all she had just confessed, questioned her about it, reflected her sorrow back to her. She denied it all, remembered nothing. Said that somehow she had found herself in a boat that landed on my beach. One could never tell how the winds and tides would direct a bow. That she and I had been spending the night in each other’s arms, kissing, smoking, enjoying the sunset and the stars.

I wasn’t to worry, she would keep our little secret from her husband, I was safe.

She took one of my cigars, lit it. We passed it back and forth. Kissed in a haze of smoke. She asked me about my past, where I was from, why I was on the island, where I would go next if anywhere at all. After I gave her the same answers as before, she told me again about her life.

A new version. She was happily married to a protective man. That she had no friends because she didn’t need them. Her husband was her best friend. She loved him dearly, would sacrifice her life for him.

We fell asleep in each other’s arms. She happy, I confused as to what happened in the smoke. The next day, I told her to take my canoe. After spending just a single night in the company of another human being, I didn’t want to leave the island any time soon. I would patch up her canoe – take months to reconstruct it if necessary – and use it whenever I needed to go back to the big island.

She kissed me goodbye. Smoke under our tongues. She paddled back to the main island, or wherever, a beatific smile on her face.

A strange life of my own orchestration. What did the smoke do? Erase her memory? I could only assume. But I didn’t think on it too long, returning quickly to my habits of solitude and isolation.

A week after her departure, another boat came ashore. A woman who resembled the girl. Bearing a box of cigars. She introduced herself as the sister of the girl. I asked what had happened, fearing the husband. The girl visited her sister, told her about me, about our kiss, and my confusion about her past – my reflection to her of the horrific life she came from and had headed back to.

The sister guessed that something magical had happened, since she knew her sibling to be in an abusive marriage, but she seemed so happy after leaving me. Like a detective, the sister pieced together how her sister escaped her home and arrived on my island, not recognizing the canoe, knowing her sister would not be allowed to own one.

Why did the girl love her husband again? Something in the smoke, the sister assumed, as I had. She saw the amnesia on her sister’s face. The girl’s life had changed because of me. She was still hit and cursed daily by her husband, but the rapturous look had never left her face. She smiled as she was smacked. Lied, said that she had only visited her sister for a night.

I asked the sister if she was here to confront me, blame me for the husband’s abuse. She said no. She had a purpose of her own. She was a widow who loved her husband, a good man. That he had been dead a year, and the love that still burned inside her was consuming her. She could only ever think of suicide.

She wanted to kiss me to forget.

If it would work or not, I didn’t know. But I naively assumed that a kiss could hurt no one. A kiss of betrayal, as Brutus to Caesar, or a kiss of love, Antony to Cleopatra. Perhaps mine was a new kiss introduced to the world of love: the kiss of amnesia.

Our lips touched, and smoke was born between our mouths.

She said her heart felt light. She recalled none of her sorrow. That she knew her husband was dead, but the dead must bury the dead. The living had to stay alive. She danced in the sand around my fire. I smoked and felt joy. That a kiss of forgetting could be a good thing, that the sister would return home to bring happiness back to her life, as opposed to rowing back into her misery.

The third sister arrived on my beach a few days after that. A carton of cigarettes proffered to me before I could say hello. I recognized the two other women in her face, could guess why she was there before she spoke. Cancer was eating her from the inside. Her husband and children mourned her while she was still alive, and their sorrow cast a pall over the remnants of her life.

We kissed, exhaled our smoke, and she went home. The cancer was still

devouring her – no kiss could cure it – but she would

no longer allow it to destroy her family or herself before it was

time.

Word got around all the islands of the nation. And from one nation

to another, my magic was told. I sat in a bamboo chair given to me

as a gift. An idol, a god. Reluctant to some degree, but also accepting

of my divinity. I received gifts and never had to return to civilization.

Civilization came to me. The masses search out their god, will walk

the lengths of the earth until they find one who can appease their

greatest desires, perform a miracle, give a blessing.

Even the abusive husband of the first sister came to me. Weeping for

his sins, confused as to why his wife smiled as he hit her. Her happiness

broke through the iron of his hand, softened it, dropped him to his

knees, arms clasping the bruised legs of his wife, tears washing her

feet.

I kissed him, and his hellish self of the past was erased. They fell

in love again, and were married a second time on my beach. I played

priest.

But I had had enough. I saw the power being given to me, attracting

me to it, making me an addict. I was no god. Whether a god deifies

himself first then gains disciples, or the disciples claim him to

be their divinity, didn’t matter to me. Though I understood

better about how the holiness of the average man could be created.

I would perform no more miracles of smoke to bless or curse the afflicted.

I did not want to ascend to anyone’s heaven on a golden ladder,

nor did I want to be crucified for anyone’s definition of blasphemy.

I came to the island to be alone. I wanted to live alone, die alone,

to neither be a pariah nor a messiah to anyone.

At night, while my many pilgrims slept in the sands surrounding my

hut, I slipped down to the water. Pushed the lightest canoe away from

the armada of canoes, row boats, yachts that clogged my bay.

I paddled quietly away on still waters, drifting into the flat expanse

of the ocean, not knowing where the horizon would lead me.

Thunder broke the silence. I looked back to my old island. The volcano

was shaking the land, burning the air, exhaling a pillar of smoke

from its pinnacle. Birds exploded from tree tops and soared away.

The volcano erupted and vomited up its fire from the earth’s

belly.

I watched for just a short while. Saw the pilgrims awaken, not yet

noticing my vanishing, their eyes on the hell descending over them,

the brimstone raining down.

I turned my face away and tightened my grip on the paddle, leaned

into the stroke with my back. Paddled a metronome rhythm, pushing

ever forward, pulling back, the bow facing the moonlight rippled by

the sea.

I heard screams and cries for mercy. I ignored them. Concentrated

on the small splash of my paddle cutting through water. Breathed in

the salt air, eyes on the moon.

Every god must abandon his pilgrims to their misery. All gods come

to an end. Every once in a while a Pompeii must be frozen in time

by ash. The planet continues to turn. No god has ever saved Mankind,

nor will one ever.

This I finally understood, paddling towards the moon.

**************************************************************************